REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

Rex Bloomstein

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

“Towards the end of the Second World War the first direct evidence began to emerge of the massive crimes of Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich. People from all over Europe had been deported, starved, used as slave labour, tortured to death and killed in gas chambers. They were Jews, Poles, Serbs, Gypsies, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Communists, Democrats - any opponent of the Nazi regime. It was the Allied forces who first entered the Concentration Camps. Without warning they confronted scenes of horror beyond the imagination.” These were the opening words of my commentary on the film.

It was the testimonies, the experiences, of these ordinary servicemen and women, who had become eye-witnesses to the truth of the Holocaust, that I wanted to concentrate on.

By 1945, American, British and Russian forces had entered and liberated the concentration camps. They were confronted by piles of dead and emaciated bodies, scenes of appalling conditions, neglect, starvation as well as brutality. However, the machinery of extermination was never filmed as it took place - it was strictly forbidden. So the famous footage that Allied cameramen took is essentially about the breakdown of the camp system under enormous pressure from the Allies’ advance.

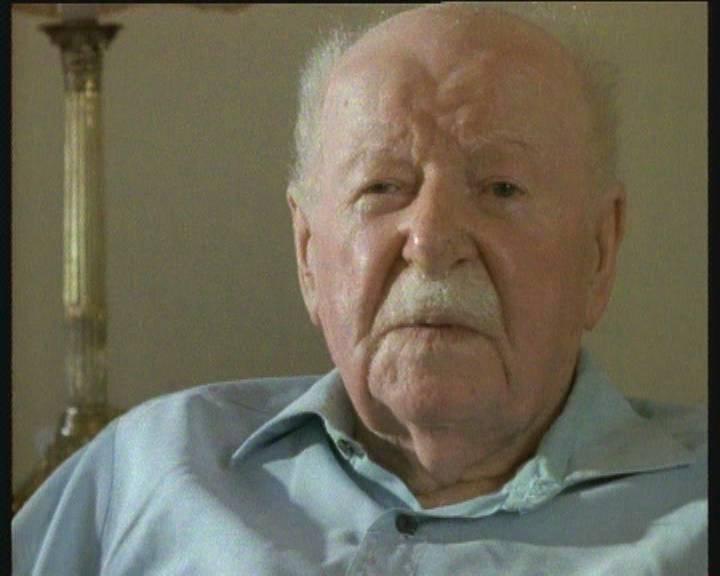

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the end of the Second World War, Channel 4 created a season marking this and commissioned a film I suggested - Liberation. The film was broadcast without any commercial breaks. In it, I interviewed servicemen and women who first entered the gates of Hell. A number had never spoken publicly about it before. One interview with a former American GI was particularly distressing and is the most graphic account of that experience that I encountered. After we finished he told me of his relief and that he had no regrets and wanted his interview to be seen.

“Living Memories Of Holocaust Death

We have seen these pictures before. We have heard these stories. They will not go away.

On anniversaries of the horrors, in history classes, at museums, we have come to know the footage too well: the bulldozers pushing emaciated bodies into a pit, mounds of shoes, piles of spectacles, corpses stacked like firewood, ready for disposal.

Nightmare’s End: The Liberation of the Camps, a 70-minute documentary premiering on the Discovery Channel tomorrow at 9pm and airing again at midnight, tells 10 more of the Holocaust’s millions of stories, this time from the perspective of the American, British and Soviet soldiers who first entered the Nazi concentration camps 50 springs ago.

This is a British documentary, and so the soldiers are permitted the time to breath and remember that American network TV values would not allow. No celebrity journalist poked his face into the tale, no coiffed anchor coaxes false emotion out of memories that require no embellishment.

Kay Bonner Nee, who served with the US Army Special Services, tells of her rush to help the starved prisoners she found inside the gates of Buchenwald. Gingerly, she admits she is haunted even now by the fact that she may have hastened the deaths of some camp victims by giving them K-rations. Their ravaged systems could not handle the rich chocolate and cheese Nee handed them out of kindness and helplessness.

‘Emotionally’, she says, ‘I never left Buchenwald’.

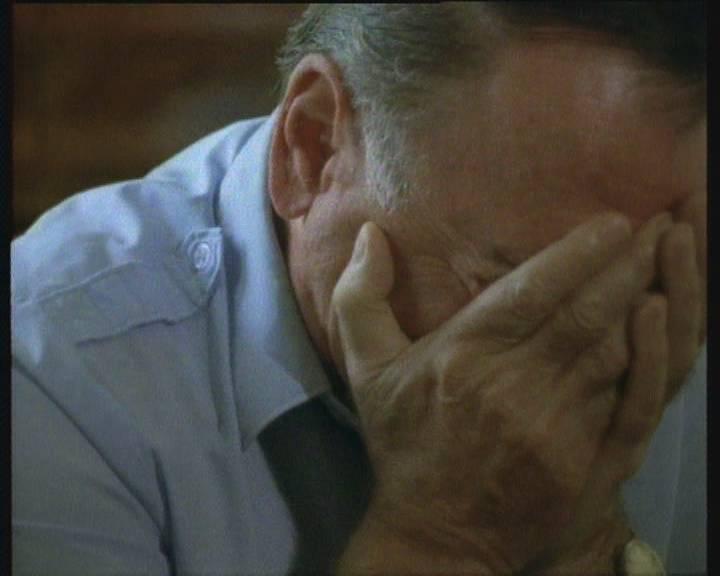

Those who witnessed the inferno are angry even now. They shake with sobs. Their jaws drop with incomprehension as they contemplate the phenomenon of Holocaust denial.

Felix Sparks, an American lieutenant colonel who led the 45th Infantry Division in Dachau, tells how his men reacted to the discovery of 39 boxcars filled with skeletal bodies. ‘My troops became extremely angry. Some threw up. Some of the I Company men simply went berserk’. One American soldier opened fire on a group of captured SS guards, killing 12 before Sparks could stop him.

These are the final years of first-hand accounts, and independent film-maker Rex Bloomstein deserves credit for seeing several powerful stories. More dramatic stories, better told, can be seen at the US Holocaust Museum, but there is much to be said for transmitting these reminders into American living rooms.

‘Memory should be permitted to sink in the sediment of time’, Guenther Gillessen told an audience of Germans, Americans and Israelis not long ago. A leading conservative newspaper editor, he is one of a growing number of respected German intellectuals arguing that documentaries such as Nightmare’s End, films such as Schindler’s List and museums such as Washington’s should be banned.

Gillessen argues for ‘a new taboo’ against photographic or film depictions of the Holocaust. ‘These awful crimes should not be permitted to become the pivot of our lives or the lives of our children’, he said. ‘It is a blessing and not a curse that human nature is apt to forget’.

Nightmare’s End concludes with the accounts of two German American soldiers who helped liberate camps in Germany and Austria. Werner Ellmann saw the bloodstained meat hooks on the walls of Mauthausen, the bodies piled up, ready for incineration.

‘I wanted to go out and kill every German I could find’, he says. He fled the camp and found some farmers outside the gates. ‘I said, ‘What goes on in that camp?’ And they said, ‘We don’t know’. And I just wanted to shoot those people, right then and there. That you can be 100 yards from that camp, smelling what I’m smelling, and tell me they don’t know what’s going on’.

Fifty years later, Ellmann’s two brothers, one American and one German, are Holocaust deniers. We have seen the pictures before. We should see them again.” - THE WASHINGTON POST, Marc Fisher

“Nightmare’s End: The Liberation Of The Camps

Half a century after the Allies pried open Hitler’s dirtiest secret, producer-director Rex Bloomstein brings forth a new and brilliant angle on the concentration camps in Poland, Austria and Germany: Remembrances by Allied service individuals who were among the first to step into the ghastliness. From a Polish-American soldier who witnessed Poland’s Majdanek to a German-born American soldier who helped crack open the last-built slaughterhouse at Mauthausen in Austria, the only word to describe the sights is horror. Horror, yet more horror.

As each testifier reports on what he saw, the extraordinary dock illustrates the appalling words with archival film (a few feet, surprisingly, in color) and stills of the interviewees from that period. German civilians file past bodies laid out in a town square followed by dead-eyed SS officers refusing to look at what they had done; former forced labourers and soldiers drag naked corpses towards mass graves.

Some footage may look familiar, but hearing these witnesses recount first impressions proves a genuine shocker. Bloomstein is unsparing in the important documentary, allowing unhurried recollections.

Fifty years later the witnesses still express undiminished dismay. Some weep, some choke recalling what they saw.

Among the speakers, a British brigadier remembers Bergen-Belsen, where an ‘immaculate German woman’ stalked the grounds with her Alsatian known for devouring an occasional infant. He remembers, too, Hitler Youth members shooting up prisoners caught on a barbed-wire fence.

An American colonel, on discovering Dachau near Munich, states that Allied soldiers had no inkling of concentration camps until he and his men came across a rail spur with 39 boxcars crammed with bodies. Once liberated, the ex-prisoners ripped apart camp informants with their hands.

Former US Army engineer Michael Calendrillo breaks down recalling what he saw at Ohrdruf in beautiful, springtime southeast Germany shortly after the place was liberated.

The Allied finders of Ohrdruf, members of the 355th infantry regiment, discovered an American pilot stretched out on a litter under a white sheet, a handful of yellow flowers laid atop his chest, and a note scratched by a fellow prisoner, ‘pilot from N. Jersey’; he’d been killed by a German guard, and the inside of his gaping mouth, where the bullet had entered, was purple.

Newsreels capture Calendrillo’s memories of the corpses, of EIsenhower and Third Army commander Patton visiting the camp days later. He also talks about a liberated prisoner who described life in the camp.

Actually, the only living person found in the camp was absently racing back and forth behind the fence. He’s glimpsed in a scene directly after a shot of Ike surveying the carnage. Still wearing the cotton uniform with vertical stripes, he’s led away from the brass and out of the picture by a GI.

Not mentioned is that Ohrdruf, where mostly Slavs were imprisoned, was unique in that a Wehrmacht camp, vacated just before the Allies arrived, stood atop a hill from which officer candidates could see into Ohrdruf. On another hill overlooking the camp stands a 1933-built mansion owned by a German chemical baron; he and his family left before the Allies hit the scene. The former engineer tells of troops bringing the town of Ohrdruf’s mayor and his wife to view the massacre; disclaiming knowledge of the camp activities, the couple hanged themselves that night. Calendrillo has suffered periodic nightmares since 1945, adding ‘You’ve gotta stop things before they even get started!’

A German-born American soldier vividly remembers Mauthausen and its meat hooks and furnaces. Docu shows a quarry where prisoners repeatedly carried rocks up 180 steps until they died. He was appalled that local citizens denied any knowledge of the huge camp despite the constant foul odor of burning flesh in the air.

Bloomstein has created a profound, invaluable contribution to the study of Nazi barbarism. Program, exceptionally organised and edited, aired in the UK last January. Unlike so many TV films and major features sidestepping the issue of German participation, Nightmare’s witnesses speak out about the perpetrated evil.

Now, with the neo-Nazi cells reportedly metastasising, there are those who deny the Holocaust too place or don’t know that there were camps in Germany itself. The GI who saw Ohrdruf groans, ‘If anyone didn’t believe this happened, I wish they were with us for a few seconds to see’.

Bloomstein’s purpose has been brilliantly accomplished.” - VARIETY, Tony Scott

“If you watch one programme in the current spate about the Holocaust, watch Liberation… It is a complex, compelling documentary that eschews music and commercial breaks so that we can concentrate on the stark message it delivers with great force.” - TIME OUT

“The visual footage of Nazi concentration camps on the point of liberation is always shocking. Rex Bloomstein’s film draws largely on verbal testimonies taken from the liberators themselves, and is just as hard to watch. Fifty years on, men break down and sob as they describe scenes of unimaginable degradation…” - THE SUNDAY TIMES

Programme 1: ‘From The Cross To The Swastika’

The first programme outlines the survival of the Jews against centuries of accusation, discrimination, massacre and pogrom to the promise of opportunity and equality offered in the Enlightenment, only for this promise to be accompanied by the development in the 19th Century of racial Anti-Semitism. Thus the poison of hatred toward Judaism and Jews nurtured through millennia has its apotheosis in Germany in the Twentieth Century.

Programme 2: ‘Enemies Of The People’

Neil Ascherson helps set the scene to the second part of The Longest Hatred. As he says in the programme: “It’s back. And so swiftly on the heels of Europe’s beautiful year of revolution when walls fell, mouths were opened and men to men were brothers. Many did speak with the tongue of angels. Others, though, opened their mouths and let out a small, smelly breath which they had been holding for 40 years. The Jews were behind it all, they said.” The programme looks at the development of Anti-Semitism and the role it plays in the Soviet Union as it then was, Poland, Austria, France and Germany.

Programme 3: ‘Between Moses and Mohammed’

In the third part of The Longest Hatred we dealt with the paradox of Ant-Semitism in the Arab world. A range of views are heard, touching on such issues as the impact of the Holocaust in the creation of Israel and how it shaped the attitudes of Israelis to their Arab neighbours, especially the Palestinians, a number of whom appear in the programme to give their perspective. What the sale of disturbing Anti-Semitc literature in Arab countries means is also discussed from these different points of view, as is legitimate criticism of Israel being seen as a mask for Anti-Semitism.The notion of suffering is particularly explored by Hanan Ashwari, professor of English at Bir - Zeit University on the West Bank. As she says: “The unique fact of suffering is real to the Jews and the unique fact of the Palestinian’s suffering is real to me… It should give us the depth, the sensitivity, the perception to deal with each other, to reach each other in a more human way.”

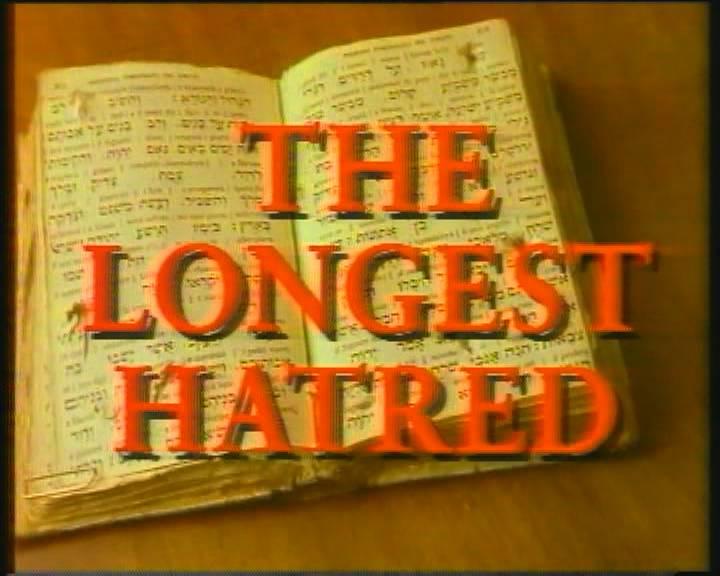

The Longest Hatred was a three-part series on the history of Anti-Semitism that had hitherto not been explored in such depth on television. We used the ‘traditional’ elements of music, commentary, interviews with historians to carry the narrative forward, still photographs and news footage. Professor Robert Wistrich wrote the script with me, bringing a masterly knowledge of the necessary historical background. Prof Wistrich subsequently wrote a book on the series called The Longest Hatred.

Most historians now agree that by the end of 1941 the Final Solution had begun and it was at the Wansee Conference in January 1942 that the details of this infamous plan were discussed and agreed.

In 1982, I made Auschwitz and the Allies, broadcast on BBC 2 and inspired by a book of the same name by the Churchill biographer, Martin Gilbert. This film at almost two hours long, shows evidence of inertia, ineptitude and downright callousness to the fate of the Jews in the British and American administrations. We reveal the reports emerging of the destruction process from 1942 onwards from Gerhardt Reigner, a Jewish official in Geneva, and the extraordinary attempt by two men, Wirba and Weztler who escaped from Auschwitz in 1944 to warn the Hungarian Jews of the fate that awaited them. Their report was dismissed and ignored.

Another factor was the timorousness of American Jewry, which failed to exert significant moral and political pressure of the Roosevelt administration. It was left mainly to Jewish extremists, such as the reviled Irgun, to actually protest and try to raise awareness. There was our discovery of an Anti-Jewish conspiracy within the US State Department. Josiah Dubois, a senior treasury department official revealed that when his department had worked out plans for the relief and rescue of Jews, these plans were systematically sabotaged by Anti-Semitic officials in the State Department. Meanwhile the death camps continued their systemised mass murder.

The Allies learned as early as 1942 what Hitler’s plans were. It was the American War Department that turned down requests to bomb Auschwitz and the railway lines leading to it at the same time as their own flying fortresses were actually bombing the IG Fahrben plant three miles from the main killing centre in Auschwitch itself. This has led to the oft asked question, could the railway lines to Auschwitz have been destroyed by the Allies? In Auschwitz and The Allies I put this to the legendary pilot, Group Captain Leonard Cheshire VC, who agreed that by 1944 the railway lines to Auschwitz could have been bombed and who says later in the interview: “that in the name of Bomber Command we would have done it… if we had received the request from the inmates themselves.” Numerous requests were made by Jewish organisations to the Allied authorities. The requests were refused.

Here are the haunting words of Auschwitz survivor Samuel Pisar:

“I think that, sitting there in Auschwitz with my comrades, we were asking ourselves: what is going on in the world outside? Is there still a world outside? There was no evidence of it. It looked as if Auschwitz was commensurate with the entire extent of the universe - nothing. We kept asking ourselves: do they know what is happening here to us? Do they care? Are there no Allied bombers to come and wipe out these tremendous railway lines and gas chambers and crematoria and hundreds of barracks and what must have been at that time one of the most populated cities of Europe, with the most transient population in all history, arriving, going to the gas chamber, constantly replenished? Where were the Allies? Was there no Red Army left? Were the British still fighting? America, where are you? All of these, unanswered questions. And that was, to us, incomprehensible. And I think that many of us must have come to the conclusion that the millennium of the Third Reich had really begun - this, from now on, would be the world for a thousand years to come.”

Excerpt form lecture Confronting The Holocaust

Anti-Semitism held a fanatical grip on Adolph Hitler and those who commanded and serviced the machinery of destruction - with the acquiescence of sections of the German population. This had devastating consequences in instigating the programme of genocide. It has to be said that even members of the Allied bureaucracies were not free of racist attitudes towards Jewish people. As one historian has put it: “there is little to celebrate in the account of British policy towards the Jews of Europe between 1939 and 1945. A few flashes of humanity by individuals lighten the general darkness. The generous impulses of a small number of officials and politicians stand out from the documents, mainly by virtue of their isolation amidst an ocean of bureaucratic indifference and lack of concern.”

“Lest We Forget

It’s a long way to Tipperary, we used to think: and to Auschwitz - and Beirut, too, for that matter. The distance, however, gets shorter by the week. Mr Begin’s ultimate bottom line - that he is doing what he is doing in Lebanon in order to make sure that what happened in Auschwitz can never happen again - is beginning to fall on ears deafened by the news from Beirut. Whether the massacre in the Palestinian camps occurred through Israeli connivance, naivety or sheer incompetence, is it beginning to look as though those who would remember history are condemned to repeat it.

‘Lest we forget’ could have been the collective title for Rex Bloomstein’s pair of programmes on the Holocaust. But remembrance is a curiously impotent state at the best of times - as the families of those killed in the Falklands must know. Even to those who were aware of them at the time, the Nazi extermination projects seemed an enormity beyond comprehension. One of Mr Bloomstein’s interviewees - who, as a young girl, had mysteriously been sent back from a camp - made the point: when she got back home, she could not persuade people that what she had seem was conceivable. In the end, she had to choose between silence and the diagnosis of insanity.

The problem remains. Nowadays we do not question the veracity or lucidity of the survivors, but we still cannot take in what they have to tell. In that sense, The Gathering (BBC2), was a disappointment, an anti-climax, a let-down. It had to be, for the whole enormity is greater than the sum of its parts, and Mr Bloomstein only had the parts. He had, for example, a woman who had given birth in Auschwitz and whose breasts had been tied by Mengele in order to ascertain how long a human infant could survive without nourishment. She told us how she had eventually killed her own child rather than allow this barbaric experiment to take its course.

She talked - and we listened - in a calm daze, a mood drained of outrage, of indignation, even of disgust. So she killed her own child; so what? Which of us would not have done the same in her position? Another woman recalled how, while employed in the camp bureaucracy, she came across her father’s corpse in a routine body-count. She said that she had been unable to weep, and seemed unsurprised by that fact. So was the viewer. It was all part of the disorder of things.

Wittgenstein once remarked that anything which could be said could be said clearly. The wisdom of that epigram lay in its implication that there are things which cannot be said. that there is a territory beyond the reach of language. The Holocaust lies somewhere out there, and 40 years of bitter experience have not brought it within our grasp. Even those of us who - like Mr Bloomstein or Bruno Bettelheim or Hannah Arendt - have the courage to reach for it find that they lack the tools for the job. There are no words or pictures which are up to it. So one is driven to assemble the parts, and survivors to speak them, and leave the viewer to sum their total in his own mind.

The fact that one cannot do it does not, however, mean that one is unaffected by the experience of attempting. It is impossible to think about Auschwitz and its implications (or, for that matter, about Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Dresden) without being brutalised, without losing one’s faith in humanity. For concentration camps - as well as nuclear weapons and firestorms - are the product of human rationality. They are practical means to politically defined ends, and the men and women who bring them to fruition are not exclusively psychopaths, although in the case of the Nazis many were.

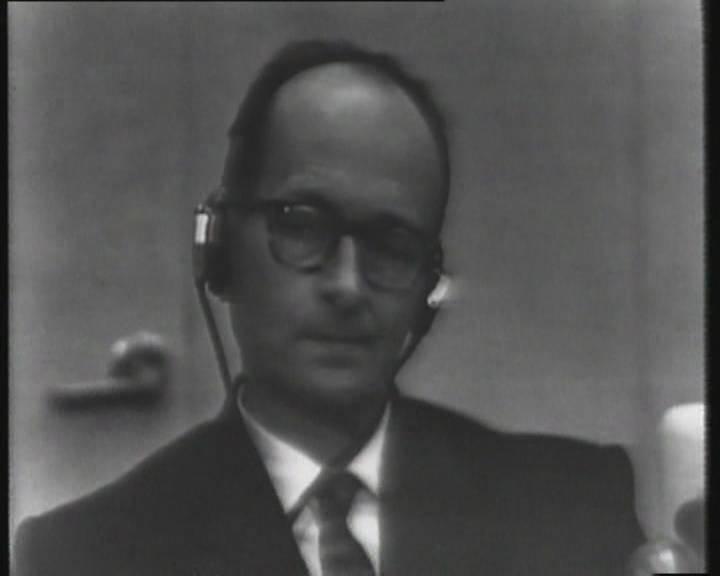

This point about the essential ‘banality of evil’, was made decades ago by Hannah Arendt, writing about the trial of Adolf Eichmann. I’d never really understood it, and it was only when watching Mr Bloomstein’s second programme, Auschwitz and the Allies (BBC2), that its full import dawned. The first salutary shock came from the mind-blowing footage of the Eichmann trial (which I hadn’t seen before), and the contrast it drew between the mild, schoolmasterish figure in the glass dock and the crimes for which he was being arraigned. This is surely what Arendt meant, and the editing of the final sequence, in which shots of Eichmann’s wryly smiling face were intercut with sequences from a film of Auschwitz made by the liberating Allied forces, made the point in a way that I will never, ever forget.

The second shock administered by Auschwitz and the Allies lay not in its revelations about the anti-Semitism of the Foreign Office and the US State Department, nor even in its account of the Hobbesian scepticism of Allied governments towards reports of the slaughter, but in its portrayal of the extent to which the Holocaust was a bureaucratic response to a political imperative. For although we all know that Auschwitz represented the application to the business of killing of the methods applied by Henry Ford to the construction of automobiles, the implications of that thought have never really sunk in. For if this model of bureaucratic rationality actually applies, then might it not have been possible to persuade the Germans simply to deport the Jews (on the grounds that, in doing so, they would be saving scarce resources for the war effort)? But for that to work, the Allies would have had to open their frontiers to the deportees - something they were never willing to do. Would they have been more accommodating if they’d known what was really going on? Mr Bloomstein’s programme was so devastating precisely because it argued, convincingly, that they did know. In which case, even the plea of simple ignorance cannot be entered in our defence.

Auschwitz and the Allies therefore forces the viewer to look into his soul, and to see there nothing more than a can of worms. - THE LISTENER, John Naughton

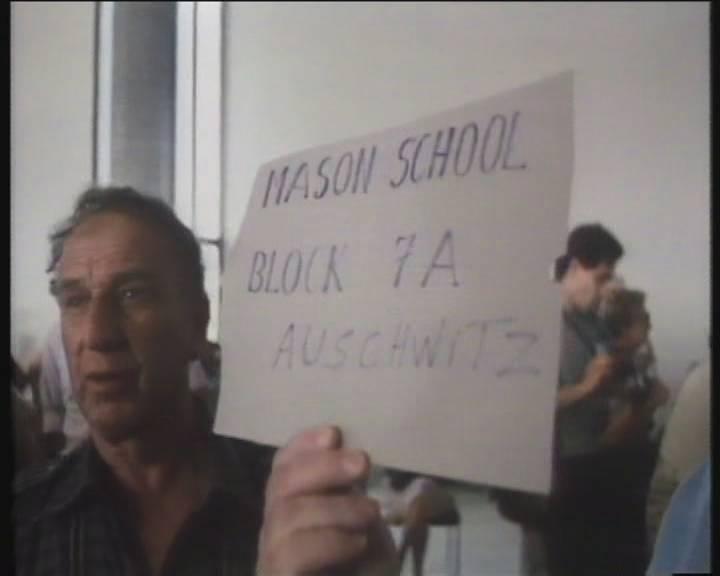

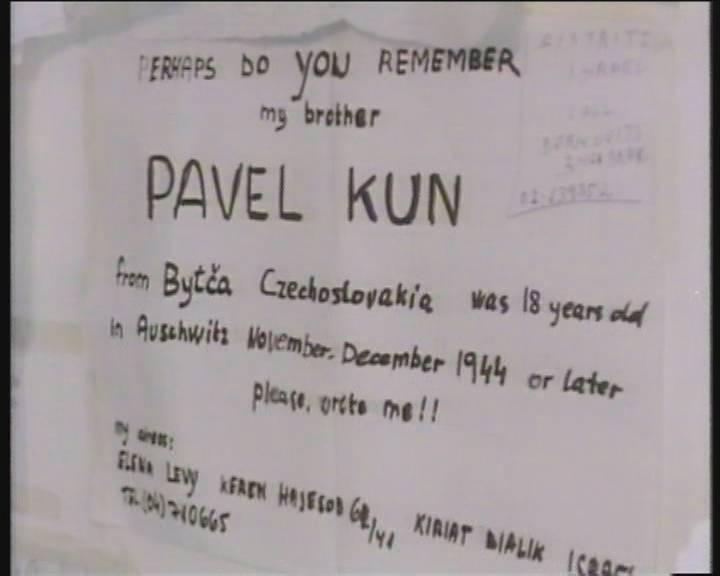

The Gathering is a record of a unique event that took place in June 1981 in Jerusalem. After years of preparation, Jewish men and women from 21 countries met for a once-only occasion - to celebrate their survival from Hitler’s death camps, and to remind the world that the unprecedented crime of genocide should never be forgotten. With modern aids such as computers, the underlying hope for these survivors is that relatives and friends long thought annihilated in the Holocaust might still be alive and here in Jerusalem. But this is also a media event, with film and video crews hungry to capture the poignance of the occasion, and under their obsessive scrutiny, they search for these dramatic moments when friends and relatives, brothers, sisters and cousins might recognise each other after 40 years of separation.

Our film mingles elation with despair as we hear of the scale of the personal tragedy that engulfed whole families, villages, towns and cities and that remind us of what is irredeemably lost. The film is interlaced with the testimonies of those survivors who experienced life and witnessed death in Auschwitz and other camps: several had never spoken before about their experiences, such as Helena Markovitch, rescued by an SS Officer from certain death in the gas chamber; Aurelia Pollak, who eventually realised the significance of a barrack full of toys; Lilli Kqpechy, who was told ‘three typing errors a day, and you go up the chimney”. There is also Ruth Elias, whose breasts were bound so that she could not feed her newly born daughter, as part of Dr Mengele’s experiments, and one of the authentic heroines of Auschwitz - Dr Gisella Perl who aborted hundreds of women so that they might survive. The film begins and ends with the story of Jona Malleyron, who, after years in a concentration camp, reaches Palestine in 1944, only to be confronted by disbelief by her own family and friends.

“The Gathering (BBC2) opened with the memories of a survivor, Jona Malleyron: ‘My mother was unconscious. My grandmother was lying on the floor… My mother remained unconscious for seventeen days, then she died’.

She escaped from a German concentration camp and brought back news from the Inferno. She sat in front of the camera, bathed in a light as harsh as the revelation of her own suffering, in direct and unadorned speech. This is a dramatic documentary technique which the producer of this programme, Rex Bloomstein, has always used to great effect. We see the speaker naked, as it were.

When Jona Malleyron reached Palestine, in 1944, no one believed her stories of the horrors in Europe. ‘I thought that was going to be my haven, but I was made to feel a liar’. The truth was not credible because it was, literally, unacceptable.

In our time, however, by the cruel impercipience of history, that truth has become almost too easily accepted. The term ‘holocaust’ is now used indiscriminately as a catchphrase and even the images themselves, as a result of their exposure on television principally, have reached a dull, dutiful and secondary level of public consciousness.

The Gathering itself provided evidence of this. It took its title from a meeting of European Jews in Jerusalem last year; they had come to bear witness to their sufferings and survival, and also to search for old friends or for members of their dispersed families. It was, frankly, a ‘media event’ with American reporters thrusting their microphones and cameras into the recesses of private grief: ‘Do you know each other… tell us about it’. One man could not bear the intrusion any longer and turned away from the microphone in tears. ‘He’s had enough’, a friend said, almost apologetically.

But the title of the programme was in some respects a misnomer, since the burden of this documentary consisted of a series of interviews with the survivors of the death camps. Who could watch them without turning away from the screen in horror and in shame? A mother’s breasts were bound together, and she watched her baby starve to death beside her. Pregnant women were used for experiments in vivisection. A typist - ‘three mistakes a day and you go up the chimney,’ she was told - heard terrible screams behind a closed door, screams ‘like an animal that is deadly hurt’. Her account of what she saw behind that door urned blood to ice.

These experiences cannot, quite simply, be taken in. And it is at this level that it becomes important to consider the role of television in employing them. Does the repetition of horrors inhibit reflection, and block the mind with unassimilable words and images: does it, in other words, act as an anaesthetic? It is possible, after all, that if you assault the mind and imagination in this way, the effect will be the opposite of that which the programme makers intended.

This is something which Mr Bloomstein himself must have considered, since it leads to general questions about the nature of television as an historical or documentary record. He must have considered, for example, the possibility that the cold eye of his camera in fact distances everything which passes in front of it, placing the memory of horrors within a frame which is as narrow as it is temporary, locating the Holocaust itself in a continuous stream of undifferentiated television images which pass and, in passing, are forgotten. Certainly there are aspects of the television age which need to be properly analysed.” - THE TIMES, Peter Ackroyd

“Out of their hell a kind of hope…

It looked like an airport arrivals hall. Everyone was waiting and looking, trying to catch sight of someone they knew once in another world, to hear a name perhaps, or recognise a face they had not seen since 1945.

It was a gathering of survivors: thousands of middle-aged and elderly people who had survived the Nazi death camps.

It was a reunion of men and women who shared the common experience of having lived through systematic and institutionalised evil on a scale which grows no easier to comprehend no matter how frequently we are reminded of it.

It was also a media festival as the prying, prurient lenses of video and film cameras weaved among the seekers, hoping to catch that moment when brother recognises brother, or father sees daughter for the first time in 36 years.

It was a bazaar for the lost and found, for the generation of European Jews who are still seeking to make some final order of their shattered lives.

Made in Jerusalem last year The Gathering (BBC2) was more than a film about loss, never-forgotten grief and shuddering nightmares. It was also, I think, about hope, about some kind of human tenacity which survived throughout the most terrible torment.

A wall was covered in messages, last desperate hopes that someone, somewhere may be also searching among that army of casually dressed people.

A woman found the sister she had not seen since 1945. One lived in America, the other in Germany. Words did not come easily. A computer ticked away.

The personal testimonies which were inter-cut into film of the gathering re-created a world of filth, arbitrary death and sadistic depravity.

There was the woman who gave birth to a baby in Auschwitz. A beautiful baby girl, she said; Doctor Mengele ordered her breasts to be bound up so that she could not feed it.

He was doing an experiment to see how long a baby could survive without food. He measured the infant every day. On the eighth day the mother, faced with death herself, killed her own child.

In the morning they took it away with the other corpses. There was the doctor who believed Mengele when he told her that he was providing better rations for pregnant women. She recruited some for him.

Two weeks later she discovered that he was actually carrying out vivisection on the foetuses.

And there was the woman whose job it was to make a list of the corpses’ numbers in the gas chamber and found herself looking into the face of her dead father.

Tonight producer Rex Bloomstein presents a sequel to this film when he asks the most uncomfortable question of the war: how much did the Allies know?” - THE EVENING STANDARD, Ray Connolly

“… The Gathering, BBC2’s documentary about the meeting of Holocaust survivors in Jerusalem last year. Here, in the intimate, underlie interviews, the emotional response of the speaker was crucial to the testimony. ‘A dream… you were like stone… I was dead… You had to be there to know, just for one night, you had to be there…’

The most effective witnesses were invariably women. They could talk and feel at the same time, whereas the men either broke down or turned away, wagging their fingers with a smile of pain. One woman said that when she escaped to Palestine in 1944 no one would believe her talk of ‘shootings, beatings, mass graves’. ‘I was made to feel a liar’. Well, who could believe it? Often, not even the victims themselves.

The same question was asked in geopolitical terms by Auschwitz and the Allies, the follow-up documentary on the next night. Auschwitz was incredible; the Allies were incredulous (also negligent and vindictive, in some cases). Here we saw, as a background, much of the usual footage: Eichmann smirking in his glass-shielded dock, the squat towers of the camp, men and women as thin as coat-hangers…

But if the purpose of popular history is to make you feel the weight of critical events, then The Gathering had far greater power to disturb and impress. It showed that something was salvageable from the psychotic and inexpiable riot of Nazi Germany. As the survivors recounted the last words of their dying loved ones - in camps, in cattle-trucks, in death-lines - a refrain emerged: ‘Remember who you are… Keep the name… Always remain what you are…. Survive’.

They did survive, and they were all, in their way, beautifully expressive. The stills, the footage, the facts - these are still inadequate, still incredible, still almost meaningless. But the faces of the survivors as they talked gave you some idea, and some hope, because they had survived in such resplendently human form.” -

American troops liberating Dachau concentration camp near Munich

American troops liberating Dachau concentration camp near Munich

Liberation

Liberation

Commander of US infantry units who liberated Dachau concentration camp

Commander of US infantry units who liberated Dachau concentration camp

Soviet liberator of Auschwitz, General Petrenko

Soviet liberator of Auschwitz, General Petrenko

Survivors leaving Mauthausen concentration camp

Survivors leaving Mauthausen concentration camp

Brigadier Bob Daniell, liberator of Belsen concentration camp

Brigadier Bob Daniell, liberator of Belsen concentration camp

Liberation of Buchenwald concentration camp

Liberation of Buchenwald concentration camp

Ex-US Infantryman recalling the liberation of Ordruf concentration camp

Ex-US Infantryman recalling the liberation of Ordruf concentration camp

Title over a Hebrew Bible defaced by a bullet hole caused in an attack on the main syngogue in Rome

Title over a Hebrew Bible defaced by a bullet hole caused in an attack on the main syngogue in Rome

Programme 1: Medieval depiction of Jews with identifying sign of the circle

Programme 1: Medieval depiction of Jews with identifying sign of the circle

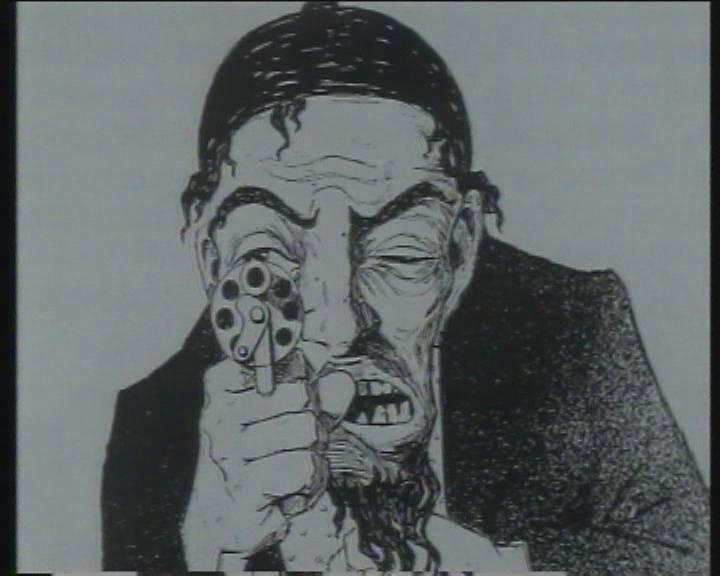

Programme 1: 20th Century caricature

Programme 1: 20th Century caricature

Programme 1: St Peters, the centre of the Roman Cathloic Church

Programme 1: St Peters, the centre of the Roman Cathloic Church

Programme 2: Modern Russian anti-Semitic caricature

Programme 2: Modern Russian anti-Semitic caricature

Programme 2: Russian neo-fascist rally

Programme 2: Russian neo-fascist rally

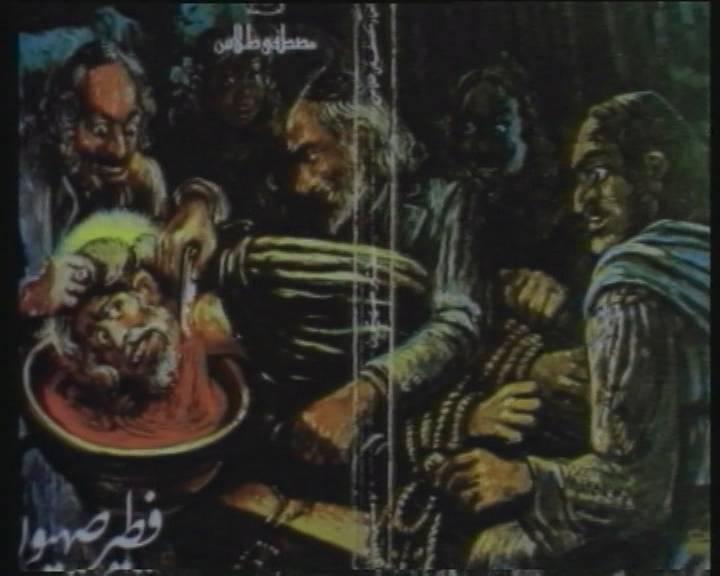

Programme 3: Depiction of ritual killing

Programme 3: Depiction of ritual killing

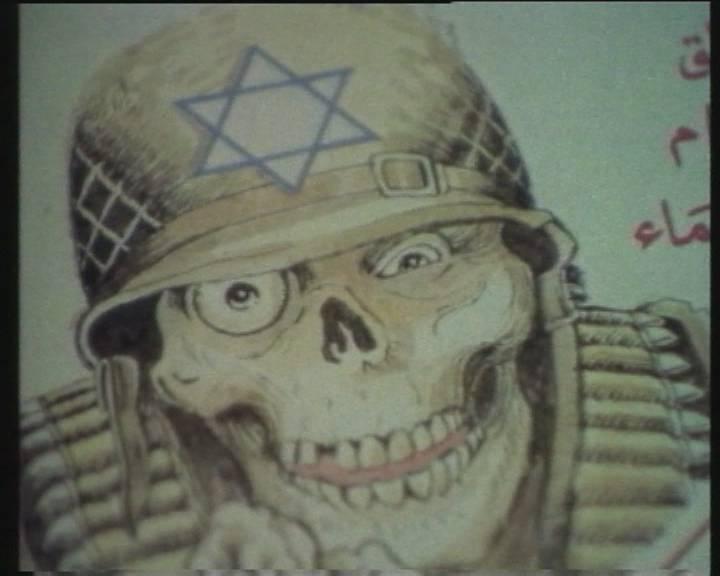

Programme 3: Arab cartoon depicting Israeli soldier

Programme 3: Arab cartoon depicting Israeli soldier

Programme 3: Hanan Ashrawi, leading Palestinian activist

Programme 3: Hanan Ashrawi, leading Palestinian activist

Programme 3: Desecration of Jewish cemetery

Programme 3: Desecration of Jewish cemetery

Title

Title

Auschwitz Birkenau - the main killing site

Auschwitz Birkenau - the main killing site

another view of Auschwitz Birkenau

another view of Auschwitz Birkenau

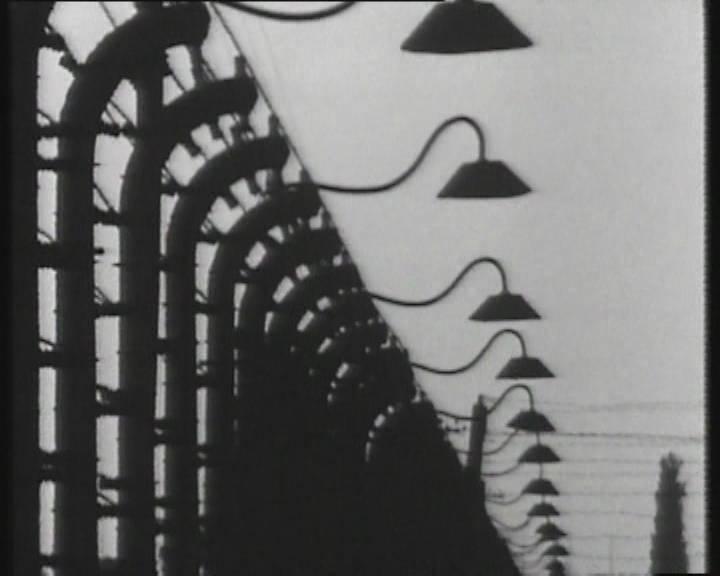

The electrified fence where so many prisoners died

The electrified fence where so many prisoners died

Allied bombs aimed at the IG Farben plant narrowly missing the main Auschwitz complex

Allied bombs aimed at the IG Farben plant narrowly missing the main Auschwitz complex

The chief functionary of the Final Solution Adolf Eichmann on trial in Jerusalem

The chief functionary of the Final Solution Adolf Eichmann on trial in Jerusalem

The opening of the Gathering

The opening of the Gathering

Outside the main hall

Outside the main hall

Lily Kopecki survivor

Lily Kopecki survivor

One of many notices pasted put up in the hall

One of many notices pasted put up in the hall

A survivor finds a link

A survivor finds a link

Discovery

Discovery

Jona Malleron survivor

Jona Malleron survivor