REXENTERTAINMENT

“The phrase that I have come to believe best sums up what the documentary film can most hope for, is to ‘undermine the simplicities’. The challenge is to present a much needed sense of flawed humanity not stereotypes.”

Rex Bloomstein

Rex Bloomstein has made over 150 single films, television documentaries and series and, in January 2012, presented his first radio documentary, Dying Inside for Radio 4. He is currently developing a number of further projects.

For full details about his work, follow the links below.

Excerpt from an interview with Jamie Bennett, now Governor of HMP Grendon Underwood, for an article in Crime, Media, Culture

JB: What was your purpose in making this film? Organizations like the Howard League have a campaign to abolish child imprisonment and to improve conditions. You have also mentioned measures such as ASBOs, and there has often been a public panic about what is perceived as ‘yobs’. What is your purpose - is it to see the abolition of child imprisonment, or is it to reform what is currently done, or is it to alter public perceptions?

RB: I think to alter public perceptions. This was not me saying we should abolish such places. Nor was it me saying reform them. In this film there was not time to consider these very important issues that you have raised and I don’t think this film was particularly the right vehicle for it, or indeed I am not even sure documentaries are the right vehicle, because these are deeply complicated issues. What I was trying to do was to humanize the subject, not untypically in relation to my other work, because I think these kids are demonized, they are made sub-human. They are often regarded as evil. There is no doubt about it, they are deeply troubled and problem kids, but it seems to me that there is a process of dehumanization which continues throughout the media, certainly the tabloid media. I felt that this film could do something not attempted before; it could present a living human being whose age is between 14 and 18, has committed numbers of crimes and offences, and who has agreed to answer questions from me. The questions I asked I think are the questions any sensible, reasonably intelligent person would ask and in doing so, deepens, even just a little, a notch, our understanding of why these kids are as they are.

JB: With Lifer: Living with Murder, you started to develop an almost exclusive use of interviews. Some of your other films, as well as interviewing offenders, have tried to explain the system. In this film you specifically focus on the people and don’t make an attempt to explain the process or the policies. Was that a deliberate choice on your part?

RB: Yes. There is a price to pay for an almost total concentration on the young people. The price I paid was that there was no time for greater context, such as some of the issues you mentioned of youth justice and indeed the view that no children should be in prison at all under 18. In my view, some are very disturbed children, and they have to be in secure accommodation, if only because the public and the children themselves have to be protected. However, undoubtedly there are too many of them inside and there are huge problems in dealing with these kids. Listening to them a lot of these questions emerge, but I didn’t want to make a didactic film. I wanted to focus on the children themselves.

JB: Jean Rouch, an early Cinema Verité practitioner described how that approach was most effective when dealing with marginalized figures. He described the camera as a window in and a window out: a window in for society to hear these people, and a window out by providing an opportunity for these people to be heard. Your films appear to be deliberately giving a voice to people who aren’t heard and don’t have an opportunity to be heard.

RB: That is very well put, and I would very much subscribe to Jean Rouch’s view as you have expressed it. These are marginal figures, demonized figures, and they are presented as very threatening figures in our society today. People are frightened and these fears and anxieties are leading politicians to over-react and to encourage the use of custody far too readily. It seemed to me that many of the issues and patterns of behaviour that emerge from the interviews are ones that people are dealing with all the time, but the extraordinary thing is that in each case there is a unique combination of factors that makes that kid who they are. In my attempt to humanize, I want to bring out the uniqueness of each of those individual cases, as well as building a sense of the familiar and destructive patterns that these kids have experienced. Almost all of them have a disruptive family life, are socially excluded, have problems at school, start criminality early, experience peer-group pressure, and gain an emotional response from the crime. The end result is that all of them are prone to violence. However, there isn’t one factor that explains why this kid did what he did; it is a cluster. What I have done in concentrating on the children themselves is to give you the audience a glimpse of the person behind the offence – their feelings, history and attitude.

The problems of breaking the cycle of criminality echoed in my most recent film on crime and punishment, Kids Behind Bars. The numbers of young offenders in custody in this country have been reduced, but remain amongst the highest in Europe and are a continuing cause for concern.

This film was made with the help of the Youth Justice Boar and was set in Castington Young Offenders Institution and Aycliffe YOI. At its heart, are a series of encounters between myself, largely unseen but heard off-camera, and a number of young offenders.

In making the film we had to deal with victim issues, parental issues, and staff issues. All had to be overcome. Because of the constraints, it meant the interview became central and observational filming less possible. My questioning was direct, uncomfortable and uncompromising; and so were the answers.

“The first thing you notice is their dead-eyed look. The young prisoners in Rex Bloomstein’s film are almost always hard, inarticulate, yet strangely able to justify their crimes… The documentary is uncomfortable but compulsive viewing. It’s hard to know what the correct reaction should be: perhaps it is fear.” - THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

“Bloomstein says of his film, ‘Kids Behind Bars reveals the complexity of a group of troubled and troubling young people. I wanted to shine a light on the individuals that lie behind the headlines and the stereotypes.’ This is exactly what he has achieved in this excellent documentary, but be warned: it does make for extremely harrowing viewing.” - THE OBSERVER

“Rex Bloomstein’s bleak film about young offenders’ institutions in the North east leaves one with a sense of hopelessness.” - THE INDEPENDENT

“Compassionate but never sentimental. Highly recommended.” - TIME OUT

“The best test of a civilised society, it has been said, is how it treats its prisoners. Does the same apply to how we film our prisoners? If so, then Rex Bloomstein has been a civilising influence.” - THE TIMES

“Rex Bloomstein’s Kids Behind Bars was as depressing as television gets. Which is not to say that it wasn’t a fine, penetrating, illuminating documentary… this film had the hallmarks of an expert at work.” - THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

Excerpt from an interview with Jamie Bennett, now Governor of HMP Grendon Underwood, for an article in Crime, Media, Culture

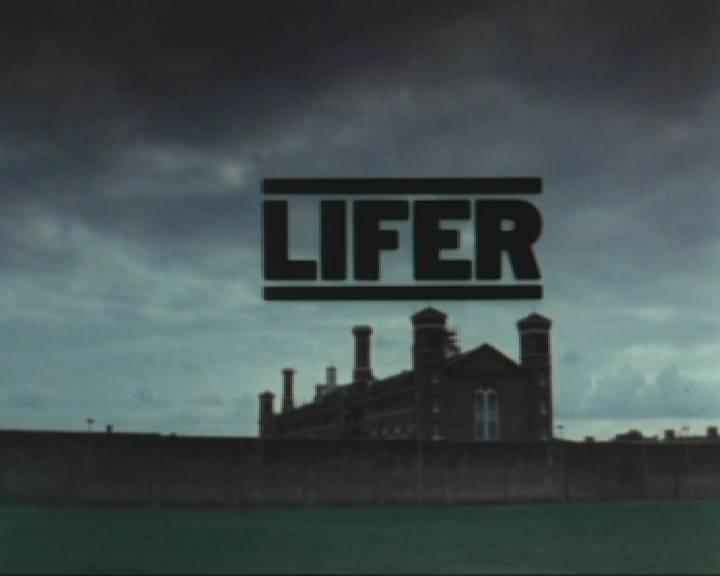

JB: Your latest film is entitled Lifer: Living with Murder. The first thing that strikes me about that is that it is a much more evocative title than a lot of your previous films. Why did you use that title?

RB: Well it was suggested to me by an historian friend. When I described to him what I was doing he said ‘oh well they are literally living with murder aren’t they’ and I thought he was absolutely right. It encapsulated rather effectively and vividly what people have to go through when you have committed a crime that like, been convicted, been given a life sentence. You literally live with the fact of murder. Virtually all the people in the film had been convicted of murder except for two, and I thought it was very attention-grabbing as well - it would get the audience to look at this pretty stark film. So two things, it was an effective way of encapsulating what the subject was about and it was also an interestingly dramatic one to get people to watch.

JB: For both Lifer: Living with Murder and Strangeways Revisited, you went back 20 years later and interviewed people that you had previously interviewed. How did you manage to track these people down?

RB: Well, it was hugely complicated. The Prison and Probation Services were very helpful - I could never have done it without their help - and I thank them all for that, I really do. On the whole, people have been glad to support the idea of the films and take the chance that the films would be fair, accurate, compelling and above all increase people’s awareness of what was going on. But in both these films it is usually an interesting experience and quite a tough one to find people. People have moved on. I had been trying to get through to Probation Offices, Probation Services, asking the Lifer Unit to help, it took months and months, almost over a year when you are talking about 29 people being filmed in the major 2 hour film and the seven part series, 29 in all. So it took a long time, much of it in my own time, much of I wasn’t as it were on contract for, but that was the only way to do it. I don’t regret that at all - the films have had real impact.

JB: You go back to this very simple style of just filming interviews, why did you choose to do that?

RB: I wanted to retain the integrity of the way I did it before, and also I believed strongly that a lot of the fashionable tools to documentary film making were irrelevant for my purpose, and also distracting, and at its worst, meaningless frankly. I didn’t want to reconstruct. I didn’t want to have music. I didn’t want to have experts talking, interesting as they are. I didn’t want to cut it in a fast way and, with one or two exceptions, I didn’t want to dramatically light it. I wanted to observe in as naturalistic a way as I could. So, for all those reasons, I wanted to reflect what I did before. Indeed, what has been remarkable is that the austerity of the approach has been welcomed by so many people, because it is so different, so stark, so austere. I think it lent itself to the very dramatic nature of the testimony.

JB: This time the spine of the film, the arc of the film, goes from people who are still Category A and who have made very limited progress through to people who have been released and rebuilt their lives. So the spine of that film seems quite positive, it seems full of hope.

RB: Well that is a reality isn’t it, people do come out, most people come out. In the end, [we showed] nine of the people… who agreed to appear on camera. We filmed about 13 or 14 but several didn’t want to appear or be contacted at all, didn’t want to know and I fully understood and respected that. Of the nine, by coincidence, four of them at the time we filmed were still inside, the rest were on the out, so it naturally lent itself to a two-parter and of course led from Ted still Category A after 20 years, hasn’t moved on, to Trevor living his life now, a violent man, gone through so many experiences and was enjoying his freedom, trying to live with a life sentence. So there is a real journey in the films.

JB: In the film Gwilym describes how he feels like a dog on a lead and Trevor says that he cannot go out at night for fear of coming under police suspicion. Do you think that life sentence prisoners are ever free?

RB: No I don’t think they are ever free as you and I understand freedom. I think the licence is an albatross they have to live with. I suppose many of them are able to put it out of their minds, lead relatively normal lives, whatever we consider a normal life to be. But I think it is a reality that is inescapable and I think the licence with its potential threat that if your behaviour is deemed unacceptable, in whatever circumstance, you could be called back into prison, and that is something few of us have to live with. Now of course most people would think that they are lucky frankly to be outside, let alone having to live under the threat of the licence. I suspect most people will applaud the fact that the authorities have the right to bring people back if there are signs of danger.

JB: Joyce talks of victims and she says ‘it is there all the time, but I just live with it, it is not something I will ever forget’. Is that what you mean by living with murder?

RB: Yes, exactly that.

JB: What has the reaction been to Lifer: Living with Murder?

RB: A remarkable reaction really. I have had overwhelming support from the programmes, and people have been moved and interested, compelled by them and I suppose for me, I never thought it would have such an impact. I think it has made human, people who are often regarded as less than human. It’s really brought home what it is like to live with a life sentence and it has reminded us again, I think, of some of the reasons why people commit catastrophic acts of violence. In this recent Shipman affair of course people have said how unknowable they are, in the end you can never fully know why someone commits a terrible act of violence, and of course there is a lot of truth in that, but I don’t think we can give up in our search for answers, explanations, we cannot throw up our hands in the face of the human potential for violence, the challenge for all of us is to contain violence. What are the factors that make people do what they do? You mentioned before abuse, the opportunities that crime gives you, I have got people to talk about their crimes, I have got people to illustrate some of the tensions that led to it. Okay, these are glimpses, but they are not unimportant glimpses, and I think we can learn from that.

The experience of making Strangeways Revisited in 2001 led me to return to my Lifer films of the early eighties resulting in two programmes, which I called Lifer: Living With Murder.

Since 1983, there has been a dramatic increase in the Lifer population. At that time, there were around 1,700 Lifers in prison. There are now over 5,000 - twice the number for the whole of the rest of the European Community. With the help of the Lifer Unit and the Probation Service, I decided to find out what had happened to the people I filmed all those years ago. After research I discovered that of the 29 featured Lifers:

Two had been freed by the Court of Appeal;

One was in a secure mental hospital;

Six were still in jail;

Fifteen were on parole;

Three had died;

And two were on the run – one from an open prison, the other out on licence who never returned to the course he was supposed to attend.

Eventually seven men and one woman agreed to go back on camera.

There is a directness in these interviews. There is no music, dramatic lighting, short scenes, fast cutting and reconstruction. I have employed these stylistic devices less and less - deliberately adopting a pared down approach to avoid over-dramatisation and the obvious manipulation of emotions. I’ve come to believe that what we might consider truthful can be easily undermined by such techniques in what is, after all, a construct. As in any creative work it is edited, shaped, the consequence of negotiation, artifice and reality. In almost inverse proportion, the more extreme the evidence of cruelty and violence, the more austere has become my approach.

Part one of Lifer: Living With Murder featured four Lifers who had never left prison, or who had been recalled. Ted was in Wakefield and serving a life sentence for the murder of a social worker, and still Category A, as was Bob, who had murdered a young woman and was in a Special Unit in Whitemoor Prison. Then there was Steve, who had kicked a man to death, and was in the secure wing of a psychiatric hospital. Steve particularly reminds us of just how catastrophic imprisonment can be, when a combination of mental illness, an inability to conform and the full might of the system bears down upon you. The film ends with Ken, serving a life sentence for the murder of an acquaintance, preparing to leave Shepton Mallett prison on license.

Part Two of Lifer: Living With Murder looks at four Lifers who have been released back into the community on licence and who were in the main coping with their lives again 20 years later.

The film featured Gwlym who murdered his wife; Joyce, given a life sentence for the murder of a woman with an accomplice during a robbery; Peter, given life for the attempted murder of his wife; and Trevor, who had killed a man during an altercation. All of them as Lifers live with the fact that they can be recalled to prison at any time if they commit any further offence or if their behaviour is deemed a risk.

Remorse , pain and regret emerge from these interviews, as well as accounts of sometimes inexplicable explosions of violence. As always with these films my main intention was to present these people as human beings – flawed, troubled, troubling.

“Lifer: Living with Murder was a reminder that the best television is often the simplest. In 1982, the documentary-maker Rex Bloomstein interviewed a selection of prisoners who had been jailed for life. Twenty years later, he returned to see how, or if, they had changed. It was chilling …” - SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

“Above all, Lifer offers an insight into worlds filled with turbulence, waste, suffering and remorse. It is a mesmerizing programme.” - THE TIMES

“Bloomstein’s style suits the material. It’s documentary at its most pared down – no experts, no music, no reconstructions. Basically, there are mercifully few distractions from the intense human experience coming straight from the horse’s mouth.” - TIME OUT

“More than 20 years ago, Director Rex Bloomstein filmed a group of prisoners who had recently begun serving life sentences. In LIFER: LIVING WITH MURDER, Bloomstein was back within some of Britain’s bleakest prison walls to see what had become of them. It was a grimly fascinating …” - THE DAILY EXPRESS

“If the title isn’t a big enough clue you should be warned that this is strong stuff.” - THE FINANCIAL TIMES

“Uneasy, thought-provoking viewing.” - THE DAILY MAIL

I decided to return to Strangeways for a follow-up programme 20 years after the original series was broadcast. Strangeways Revisited was made for BBC 2’s Timewatch. I wanted to see how much had changed since I had filmed there in 1980, what had happened after the 1990 Strangeways riot and £80 million of refurbishment.

We managed to track down a number of former inmates, who agreed to be interviewed about the lives they had led since. Strangeways itself was undoubtedly a cleaner, safer place with in-cell sanitation, TVs and better facilities all round. But the prisoners I now interviewed on camera spoke of more violence, more stigma, less chance of rehabilitation – many of the same themes we captured all those years ago.

“It is grim viewing, yet surprisingly moments of tenderness and hope alleviate the overwhelming air of doom and menace.” - THE TIMES

“Bloomstein’s pared-down approach – no visual trickery, no Smiths songs – may be unfashionable, but his riveting second encounters with the series’ interviewees testify to the skill of his probings.” - THE SUNDAY TIMES

“Rex Bloomstein… returns to the prison to see how things have changed and tracks down former inmates and staff. With stories of sexual and physical assault, as well as redemption and real efforts to go straight, this is a tough and emotional programme.” - HELLO MAGAZINE

“In 1980, Rex Bloomstein’s Strangeways went within the walls at the Manchester prison, and won two Bafta awards as well as the Broadcasting Press Guild award. Twenty-one years on, Bloomstein revisits for Timewatch. How has the place changed? More poignantly, the stories of eight former inmates and staff are featured in the original and traced to the present day. There is one-time gangster Vinny Valente who, since 1981, has returned to jail almost a dozen times for violent offences. Vinny tells of his efforts to go straight and what happened during his time as a child in care. Terry McDonald redeemed himself from crime after her visited his critically ill daughter in hospital. Happily his daughter survived and so, too, did his marriage. Naturally, there is tragedy too.” - , Pick of the Day, Nick Griffiths

“In 1980, Rex Bloomstein blew the lid on Manchester’s Strangeways prison with his ground-breaking documentary series. Twenty-one years later, Bloomstein returns, first to catch up with some of the larger-than-life characters from his original film, which is shown here in clips. They all talk of abuse heaped upon abuse, some of which is so extreme it starts to sound like Kes meets Guy Ritchie meets Shoebox-on’t motorway. It’s hard to tell how much is exaggerated - criminals love blowing their own horns - but the facts speak for themselves. The Terror of Salford (in the original film he was 16 and in solitary after two suicide attempts) was found at the bottom of a river aged 23. If you really want to know why some people turn to crime, watch this.” - THE EVENING STANDARD, Choice

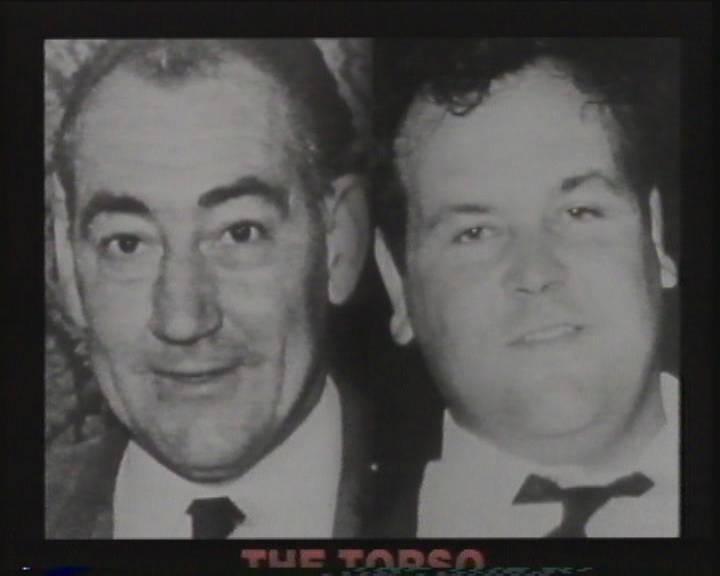

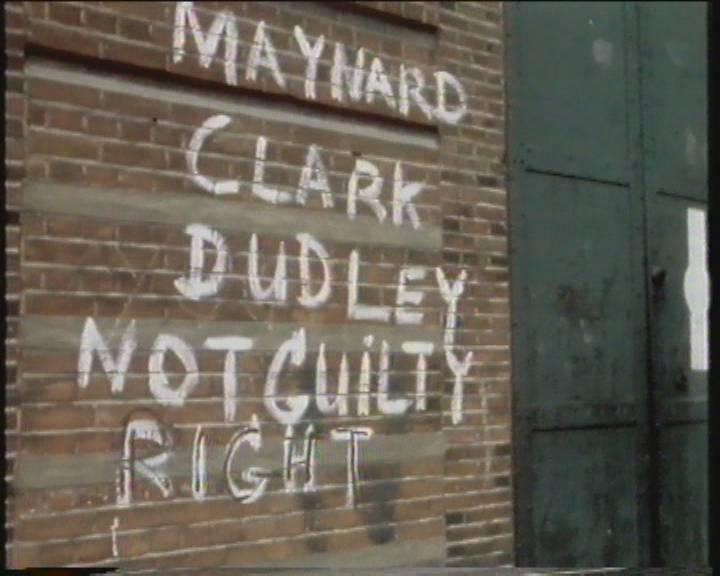

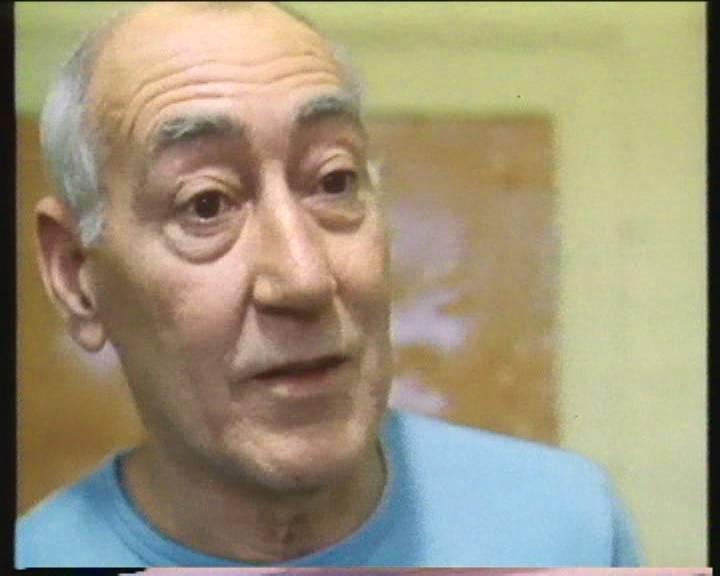

I had become aware of the campaign that Duncan Campbell, the Guardian journalist, had waged on behalf of Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard, career criminals who were convicted of of a double murder in the 1970s and both given life sentences after the longest murder trial in British legal history. Duncan was convinced, as were other journalists, that they were both victims of a miscarriage of justice - such cases were not uncommon at that time. After studying the case myself, I also became convinced of their innocence and approached Channel 4, who agreed to commission the film. Some years later their sentences were quashed by the court of Appeal and they were given compensation. Reg Dudley, who I had filmed for my Lifer programme in the early eighties, has since died.

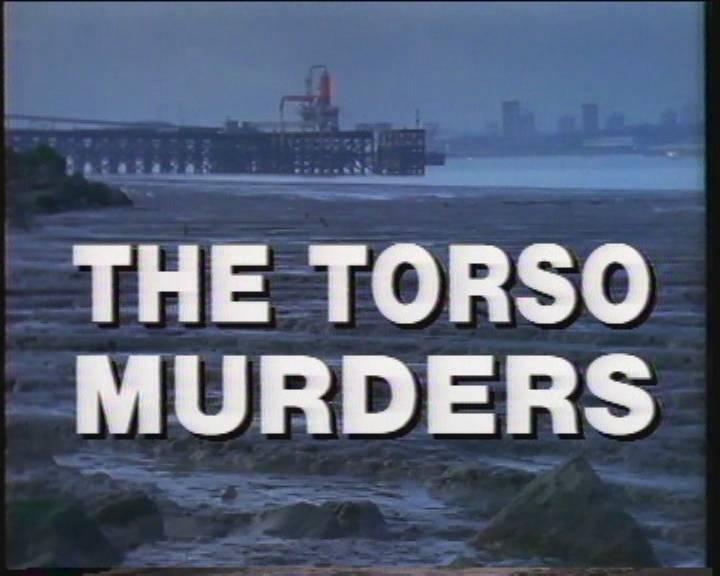

“The same, only torso

In October 1974 a headless torso was washed up on the banks of the Thames, the beginning of a series of grisly finds in the mud, body parts found to belong to North London criminal Billy Moseley. Eleven months later, the body of another London con, Mickey Cornwall, was found in a shallow grave in Hatfield. He’d been shot through the head. This is the basis of the latest in the ‘True Stories’ series, The Torso Murders, produced and directed by the eminent Rex Bloomstein, responsible for the award-winning BBC2 series, ‘Strangeways’.

Seven people were finally arrested for the two murders and tried in what was the longest murder trial in legal history. Four were found guilty, and two, Bob Maynard and Reg Dudley, still remain in prison protesting their innocence. Bloomstein’s film is a long, complex affair, but stay with it: not only is it splendidly redolent of colourful cockney crimeland types like ex-bank-robber Bobby King (‘You must be fuckin’ joking… Maynard couldn’t terrorise his own kids’) but it ends with a considerable bang.

The case of Bob Maynard is particularly distressing: having served the minimum recommended term of 15 years, he still languishes in Norwich jail unable to be released because of his continued protestations of innocence. The Home Office allowed Bloomstein to interview Maynard, but on the same day ‘refused him permission to spend a day at home. It seems as if they are giving with one hand and taking away with the other.’

The programme originated with Guardian journalist Duncan Campbell, who first wrote about the case in Time Out in 1977 and recently profiled Dudley in a newspaper piece which, says Bloomstein, triggered off his memory of featuring Reg in his earlier C4 series ‘Lifers’.

Looked at in the light of the Police and Criminal Evidence safeguards introduced recently, the convictions of Dudley and Maynard would have been thrown out before they reached the magistrate’s court, an opinion backed up by the fact that there was no physical evidence linking any of the defendants with the murders. Dudley and Maynard went down, says Campbell, ‘on verbal confessions that would have been inadmissable today and on doubtful testimony from known criminals’. Tragically and suspiciously, all the handwritten notes referring to the case were recently destroyed, but the programme provides startling new evidence from forensic linguistics expert AQ Morton of Glasgow University, whose opinion of the typewritten interviews is ‘rubbish as evidence’. Morton’s method has been applied in criminal cases both here and abroad, and suggests that their statements were altered.

Bloomstein admits that the programme loses from being unable to confront any of the police involved, ‘although Commander Bert Wickstead has made it clear that his views haven’t changed since his last interview in 1978.’ Bloomstein has ‘avoided reconstructions and dramatic soundtracks, the kind of thing which I think creeps in too much… they are appealing within the next fortnight and I just hope the programme influences things for the better.’ - TIME OUT, Steve Grant

“In 1975 Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard were given life sentences for killing two fellow villains after the longest murder trial in British history. They protested their innocence but Chief Supt Bert Wickstead, the policeman in charge of the case, had no doubts. Interviewed in the same year, however, Wickstead predicted that “some idiotic do-gooder” would reopen the case and convince a gullible public that the men were part of a wicked police frame-up. Rex Bloomstein’s film alleges just that. Even the judge conceded that oral confessions were the only evidence against the men. A defence barrister says no jury today would have convicted, indeed the case would have been thrown out by the magistrates’ court. The programme includes a new interview with Maynard, recorded this year at Norwich prison.” - THE TIMES, Choice

“Horror Stories

Thursday’s True Stories (C4) focused on the so-called “Torso Murders” of 1974, when four people were imprisoned for murder, two of whom are still inside. From extraordinary Home Office memoranda, it appears that these two - Bob Maynard and Reg Dudley - will not be released until they have “addressed their offending behaviour”, or, in other words, stopped protesting their innocence.

Though theirs was the longest murder trial in British legal history, they were convicted with no physical or forensic evidence, no eyewitnesses, no murder weapons, no signed confessions and little or no motive.

As a straightforward documentary of injustice, it would have been hard to better, but True Stories also presented a fascinating, and often rather comical, portrait of the East End underworld in the early 1970s. I particularly liked one of the crooks being called Ronnie Fright, and some of the more strait-laced interviews with ex-cons over pints of beer were unintentionally hilarious.

“‘E was always firing after Richards,” reminisced an elderly bank robber.

“Richards?” queried the interviewer.

“You’re not allowed to say it anymore,” explained the bank robber, smiling into his beer, “Richard the Thirds - birds.” - THE SUNDAY TIMES, Craig Brown

Thames Television publicity material:

This documentary affords a remarkable insight into the condition of men, women and young people who have been sentenced to life imprisonment. In Britain there are nearly 2,000 of them, out of a total prison population of over 43,000. They differ significantly from their fellow inmates, not just because of the seriousness of their crimes, but because of the nature of their sentences.

In a series of interviews, lifers talk with complete freedom about the offences, the system which contains them and the pressures of long-term imprisonment. Their experiences make compelling, and disturbing, viewing.

Lifer was a two-hour film broadcast on ITV in 1983. A year later Lifers, a series of seven 30-minute films containing further interviews with lifers was broadcast on Channel 4. In all, some 29 lifers appeared.

The unprecedented access I was given during the making of Strangeways meant that I was able to persuade the Prison Department to further allow interviews with lifers directly in their cells. These interviews revealed men, women and teenagers who had committed such crimes as murder, rape, arson - all of which had resulted in a life sentence. They were free to talk to me without supervision, though I remember prison officers insisted that the door of the cell had to be left open if they were Cat As, the highest security category. Lifers spoke of what happened, and why, of lessons that could be drawn, of having to cope with the long years ahead. It seemed to me they spoke to us of the darkness in human behaviour and what we as human beings are capable of.

Filming took place in several prisons with lifers in different stages of their sentences. Some just starting, some half way through, some on the way out on life licence. Their stories varied so much: Dennis who wanted to die in prison; Dave who thought he would never be released; Alistair who couldn’t understand why he was in prison at all.

Excerpt from Rex Bloomstein’s introduction to a screening of Lifer at the Institute of Psycho-Analysis:

Why did these Lifers agree to go on camera? An expiation, a rare opportunity to say something about that moment of explosive hatred? A baring of the soul? The possibility to show the authorities the necessary remorse? Or simply that they were asked?

What emerged were part-confessionals; anguished, self-serving, intense and perhaps revelatory. In their directness I believe they present a challenge. The challenge to make something meaningful of actions condemned by society and which reflect such disturbing aspects of human behaviour.

I hope just a little they might have ‘undermined the simplicitie

“… Programme-makers are entitled not to defend their work if they don’t want to (and we are entitled to draw our own conclusion), but I think they should be encouraged to. Perhaps 10 per cent of their fee could be withheld until it becomes clear whether or not their subsequent presence is required.

Rex Bloomstein, for instance, dutifully turned up to face a rather overstaffed panel of experts after the showing of his film Lifer (Thames), though doubtless the knowledge that he’d made an extraordinarily interesting documentary gave him confidence. It was fuelled by the strong by simple desire to inform (What exactly is a life sentence? Who gets one? How does it work?), and had presentation to match: much of the film consisted of lifers talking straight (or deviously) to camera.

Bloomstein wasn’t allowed to interview terrorists or Krays; but he got a good spread of killers, who on the whole looked slightly less villainous than, say, a line-up of young British novelists. There was a transvestite homosexual (‘There’s a big demand for people like me in prison’); the no-hoper who thought euthanasia ought to be available to murderers; the psychopath who hammered in a homosexual’s skull and remarked, ‘If society could relate to what I did… ‘; and the ordinary domestic killer who was drunkenly playing games with a gun and shot someone he loved (in America he’s called William Burroughs; here he gets life).

They told their grisly stories persuasively, though of course prison gives you time to work on your persuasiveness. One irate ex-con rang in to comment: ‘The prisoners are playing a game for the TV - I’d have done the same’. They’re also, of course, playing a game for themselves; as a parole board psychiatrist pointed out, lifers are masters of self-deception. Trying to unpeel the onion layers was one challenge presented by this impressive, sober and admirably unslanted film. For once, too, the prison service emerged in a favourable and uncaricaturing light.” - THE OBSERVER, Julian Barnes

“Human life, prison life

Hannah Arendt’s famous phrase ‘the banality of evil’ was coined to describe the crimes of the Nazi era, crimes more heinous than those explored in Rex Bloomstein’s television film Lifer which was screened on Tuesday night. But the phrase came irresistibly to mind during this poignant, often chilling, constantly riveting documentary. Here were men and women who had committed murder, the most abhorrent crime of all, talking articulately about their crimes and their reactions to their punishment, displaying variously insight, self-delusion, pain, intelligence, vulnerability, despair, even remorse. In short, they were revealed as recognisable individuals, and in that lay the film’s most valuable contribution to the penal policy debate. For it is difficult to face the fact that we lock away for 10, 15, 20 years or more people with whom we can perhaps identify, even sympathise. It is far easier to think of such criminals in the larger than life terms of lurid newspaper headlines which present them as monsters, aberrations from nature, who can therefore be conveniently forgotten as soon as they have disappeared from the dock. They may have committed aberrant acts, abhorrent offences, but they are still people. There was eloquent testimony to the fact that this is a difficult truth to swallow after the programme, when of the hundreds of viewers who rang into the talking heads debate after the film, the majority seemed to be appalled at the apparently sympathetic manner in which these criminals had been interviewed.

Yet, 18 years after the abolition of the death penalty, it is surely time we adopted a more reasoned approach to the disturbing questions raised by sentences of life imprisonment. In 1957, there were 140 prisoners serving life sentences in our gaols. In 1981, there were 1,750; by 1985, it is estimated there will be around 2,000. In part, this is explained by the abolition of the death penalty. But some of the increase is because life sentences are being used more and more for lesser offences such as wounding with intent, rape or arson.

Life is the maximum sentence for such offences; for murder, it is mandatory. There is a strong case for saying that it should be the maximum for murder as well. For murder should not be seen as a homogenous offence; some murders are worse than others. Who would say that the man who killed his wife committed as grave an offence as the terrorist who blew up the pub? Who would claim that those who commit ‘crimes of passion’ are as dangerous to the rest of us as the psychopathic armed robber? Yet mandatory life sentences allow no such distinctions. The mental suffering caused to prisoner and family by the indeterminate nature of the sentence is spread impartially among people who kill their wives’ lovers and people who blow up public houses. The Advisory Council on the Penal System, the Butler committee and half of the Criminal Law Revision Committee thought this was wrong. Perhaps Mr Bloomstein’s film will add urgency to their arguments.” -

“... splendid and absorbing… This is the first time that life sentence prisoners have been allowed to speak freely on television and the result is revelatory.” - THE SUNDAY TIMES

“... a remarkable series of interviews, reaching beyond mere voyeurism… an extraordinarily interesting documentary… impressive, sober and admirably unslanted.” - THE OBSERVER

“Sometimes the camera draws more out of themthan the authorities ever did.” - THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH

“This was the richness of television…” - THE MAIL ON SUNDAY

“... superb…a series of near hypnotic interviews…” - THE EVENING STANDARD

“... the most gripping documentary in ages…” - THE DAILY MIRROR

“This was a chilling, yet riveting programme.” - MORNING STAR

“Provides a penetrating insight…” - THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

“Rex Bloomstein’s documentary must have altered some easy pre-conceptions about what kind of people are capable of taking an innocent life.”- THE DAILY MAIL

“Totally engrossing, totally fascinating achievement… LIFER was a remarkable in television journalism.” - THE DAILY EXPRESS

“LIFER was strikingly open and honest and elegiacally beautiful.”- THE GUARDIAN

“Fascinating …….absorbing.”- THE TIMES

“... so watchable. It made marvellous use of the eloquence of men who have spent decades focused on a single ‘dramatic’ moment in their lives, from which everything spreads outwards, as in a play”. - THE NEW STATESMAN

“... quite simply the best film of its kind I’ve ever watched. Great stuff and all the better for being kept simple.” - BROADCAST

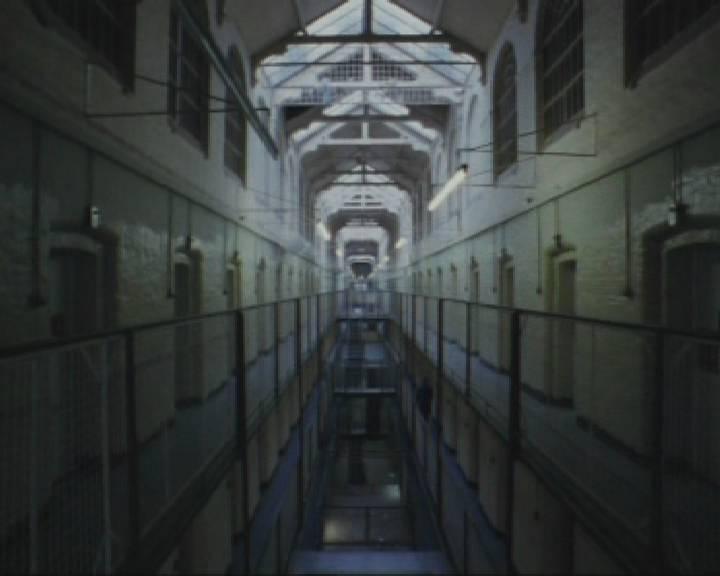

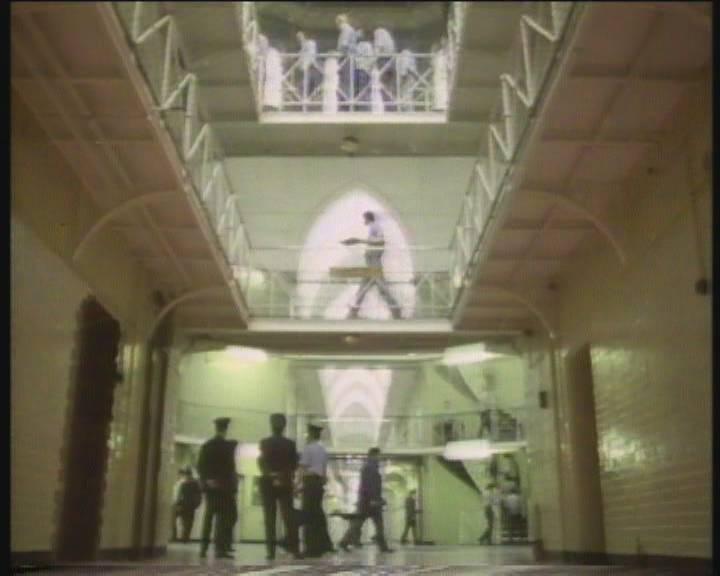

Our eight 40-minute programs were based on Manchester’s giant local prison known as Strangeways. The access we were given was unprecedented. Thanks to the courage and integrity of Norman Brown, the Governor, no part of the prison was off-limits to our camera.

The series revealed the squalid realities of a vastly overcrowded Victorian jail, with inmates living three to a cell, with a bucket in the corner as a toilet. We met fine defaulters, thieves, drug dealers and sex offenders. We witnessed prison justice with an allegation of brutality against a prison officer; filmed life as it was lived on the punishment block and experienced the poignancy of ‘Xmas’ day in jail. We looked at the prison from the different perspectives of ‘screws’ and ‘cons’ and called the first programme in the series A Human Warehouse – a title that perhaps aptly summed up Strangeways and many of our other local prisons in England and Wales, both at that time and to the present day.

Excerpt from my lecture, Crime and the Camera:

By the end of the 1970s my most ambitious aim was to document the prison itself. Up till then it wasn’t documentary that offered the best insight into prison life, but that marvellous comedy series Porridge.

But what was prison life really like? At that time there was enormous concern at the impact of overcrowding within the prison system where, amongst others, fine defaulters, thieves of every type and description, drug dealers, etc jostled with a minority of violent offenders. The prison population had reached the shocking total of 47,000 people. (It is now over 84,000).

I think this was a factor in senior prison management being prepared to consider my request for a major fly-on-the wall -series, where nothing was off limits. This was the key to capturing the realities as far as it was possible to do so - the willingness to risk the cold eye of the camera. By this time my work was known, as was my insistence that in the end it was a question of trust, because editorial control lay only with me and the broadcaster. It had to.

So it was, in late 1979, after intense negotiations on all sides, I was finally given unprecedented access to film inside HMP Manchester – better known as Strangeways. A chance to reveal the daily realities of an overcrowded, giant local Victorian gaol as it had never been seen before. It is why I called the first episode, A Human Warehouse. The titles of other episodes reveal the different perspectives that we uncovered within this extraordinary community: Screws, Cons, They Call Us Beasts - the name given by other prisoners to the despised and rejected sex offenders - Borstal Boys - 15 and 16 year olds awaiting their dispersal to borstals in a separate wing within Strangeways - The Block - the punishment wing housing those who had transgressed against the system.

“Rex Bloomstein’s devastating Strangeways series ended with an account of Christmas in prison which I have no hesitation in nominating as the best single documentary of the year, and one which in 1990 will be looked hack on as a classic.The grotesque contrast between the bleakness of prison life and the efforts to introduce the trappings of Christmas celebration - religious and musical, culinary and decorative - produces an initial lump in the throat which grows to bursting point throughout the 45 minutes.” - BAFTA NOMINATION

“Strangeways ‘Xmas’

The best documentary series of 1980 bows out with the poignancy of isolation ironically underlined by the tinsel trappings of the ‘festive spirit’ inside the prison. Watch it and ponder. There is more to the real meaning of Christmas here than perhaps In any other programme currently on the box.” - THE DAILY MAIL, Elizabeth Cowley

“Packing ‘students’ into the school for crime

There are more children going into Institutions in Great Britain than in any other country in Western Europe, writes Rosalie Horner. Tonight “Strangeways”, BBC 1’s outstanding documentary series about the Manchester prison, looks at the “Borstal Boys.” The Borstal Allocation Centre at Strangeways is a prison within a prison, a sort of junior school of crime before the “student” matriculates to the big school, which tragically he almost inevitably does. In fact, a recent Parliamentary report has claimed that it is a scandal to keep young boys incarcerated in such surroundings. The place may technically qualify as an assessment centre, but with its rules, punishment block

and uniforms, it is a prison in everything but name. It holds 500 young men aged from 15 to 21 who should only be contained there for a few days, but ofter they remain for up to three months due to a shortage a space which prevents then being placed elsewhere. This extra time can often do irrevocable damage to a young person by firmly establishing him in a life of crime.” - THE EVENING STANDARD

“‘I’ve always been rejected. I’ve never been wanted. And that’s why I made myself a female, because I wanted someone I could love. A girl. All the gentleness of a girl’. The Bible lay open on the bed beside him as Roy told his tale. How he had wanted to have the operation, how his mother had told him to pack his things and go, how in desperation he had turned to the Holy Spirit and how, in return for Roy’s love, the Holy Spirit had taken away the awkward urge.

Over the past six weeks, Strangeways has shown us many strange and terrible things, but among the strangest and most terrible were some of the things shown last night. This report on the junior prison within the adult one opened with a bloodcurdling hymn of communal hate blaring from the floodlit windows, and it then cut into Roy’s humble abode. We were not told the crime that had put Roy there in the first place, but for the crime of resisting homosexual advances, a mixture of water and urine was nightly poured into his ceil.

We met a nest of jail birds, three from the same family. We doubtless glimpsed the odd psychopath. We also followed the senior medical officer on has morning rounds. ‘Morning!’ Boy stands up, naked apart from a blanket. ‘How are you this morning?’ - ‘All right, thank you.’ He had attempted suicide the day before. ‘Got it out of your system Good. You’re not prone to do this are you?’ - ‘Yes sir.’ - ‘You are? Oh.’ On, with breezy disapproval, to another cell. ‘What’s all this wrist business?’ The scar is hesitantly proffered. This inmate, it emerges, had tried to hang himself at Risley. ‘What was that for?’ - ‘I just didn’t like the place.’ - ‘You’ll be giving it a bad reputation! You look like a lively lad to me. You’re not serious are you?’ - ‘I don’t know sir.’

Yes, the mind boggled. Jean Genet would have got overexcited, Joe Orton would have felt out of a job. Dickens would have known exactly what to do. The Home Office does not know what to do. Thanks to Rex Bloomstein and his admirable team, it has once again been made clear that a great many inmates of our prisons simply should not be there.” - THE TIMES, Michael Church

“Rex Bloomstein’s exploration of Strangeways, without doubt the most searching anatomy of a single prison ever undertaken on television, tonight reveals what happens on C landing, where inmates labelled ‘beasts’ by their fellow prisoners serve out their sentences. They include the sex offenders and child batterers, a detested breed. For their own sakes they have to be kept segregated from the other prisoners - Rule 43A, we learn, is their life-line.” - THE TIMES

“Strangeways covered the Borstal-replenishment side of prison work, using more of the astonishingly revealing film which has characterised this series. This excellent production has a paradoxical effect on the viewer: for it leads one to wonder what must really go on in prison if they will allow stuff like this to be shown.” - THE OBSERVER, John Naughton

“Prisons will never be quite the same after Strangeways, Rex Bloomstein’s all-revealing fly-on-the-wall documentary series. Surely it is the most compulsive viewing of the week.

It has swept away the prejudices, destroyed the illusions. No on can ever again kid themselves that prison life is some sort of Butlins with bars, or that our prison service is staffed by neolithic bully boys.

Strangeways has been an eye-opener. Filmed without censorship and with few apparent restrictions it has, at least to this outsider, appeared to tell it as it is. The anger, the humiliations, the pettiness and above all the waste.

Last night’s film took us to ‘The Block’, the punishment and segregations landing that houses the hard cases. An appalling place seething with resentment and, even though the camera tends inevitably to prettify the picture, you could feel the brutality and sense the violence.

A man beaten up in the showers excused his black eye: ‘I slipped on a bar of soap’, Afterwards he confided to the camera that he was a victim of ‘Cons Law’, the unbreakable code that no prisoner may inform on another.

There were extraordinary, almost Hogarthian, glimpses of life inside. Barry, a compulsive sex offender who has to be kept apart from other men, played up to the camera, flirting coquettishly. Even the warders were wary, everyone seemingly sexually threatened by him.

What is surprising is not that there is trouble in prison, but that there is so little trouble. Amazingly the prison staff keep their temper and their good humour. There are a lot of jokes and friendly banter between them and the prisoners.

‘How many slices of liver of you want?’ asks a prison officer at lunchtime. ‘How many am I allowed?’ ‘Only one. It has been a bad year for liver. There has been a strike in Liverland!’

Already it has been possible to spot a good prison officer, the dedicated professional from the time-server. You can tell that against all the odds there are men there who really care.

I wish the picture of some of the other prison services was as encouraging. But there was a welfare department apparently so overloaded it had little time for tact and could barely tell one prisoner from another.

There is little chance that prisons like Strangeways can reform or rehabilitate. I doubt that it even deters the real villain. One of them said last night, after years of borstal reform schools and prisons: ‘All it does is give you a bad insight into society and make you want to get back at it’.” -

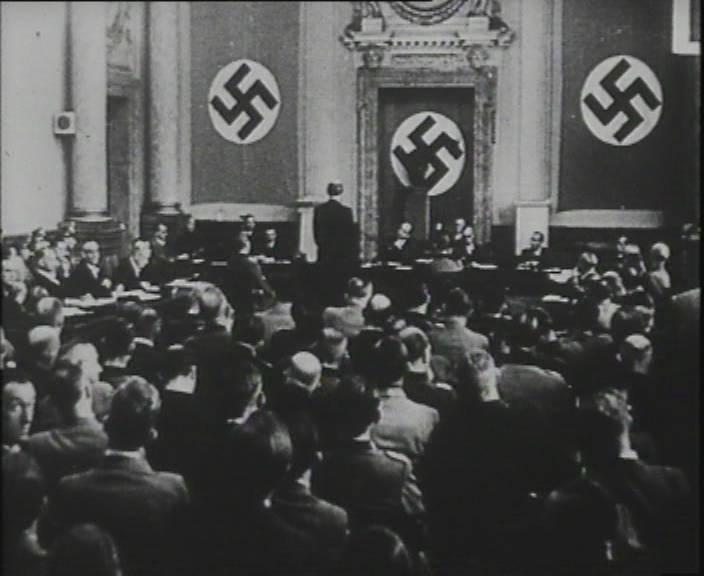

My producer for many of the films I made at the BBC was Roger Mills who, sometime in 1978, came into my office with a newspaper review of a feature documentary just screened at the Berlin Film Festival called Geheimer Reichsacher (Secret State Trial). It seemed interesting, and I obtained a copy from Chronos, the German company who had made it. The film was a potted history of World War Two, the German resistance and ‘never before seen’ footage, in synchronous sound, from the trials of the the men who plotted to overthrow the Fuhrer on 20th July 1944. This footage was immensely powerful. I travelled to Berlin and, in a cutting room, looked at the rest of the trial footage not used by Chronos in their documentary. As I watched the president of the court, the relentless and merciless Dr Roland Freisler, force army generals and officers, senior policemen, diplomats, clerics and politicians, to answer as to their role and attitude, an outline of the plot emerged. This was the film I wanted to make. I would use these extra-ordinary and dramatic fragments as the basis for a film and, with my commentary, add crucial details. To further this, I filmed in Wolfschanze, Hitler’s former headquarters in East Prussia, where the remarkable Count Claus Von Stauffenberg set the bomb designed to kill the Fuhrer under the map table. I also discovered the actual room where the trials took place – not the People’s Court as previously assumed, and which was eventually destroyed in an Allied air raid, but the Berlin Supreme Court, housed in what was then the Allied Control Building. This room had not been used since the end of the War. I quietly filmed it and it opens our film. This building is now, I am told, the Ministry of Justice.

“Traitors to Hitler (BBC2) was, you might say, produced by Joseph Goebbels and directed by Rex Bloomstein, as improbable a co-production as one could hope to see and an outstanding programme full of pain and pity.” - THE GUARDIAN

Excerpt from Rex Bloomstein’s lecture, Crime and the Camera:

The Parole system at that time in the late seventies was severely criticised as arbitrary and impenetrable. Some thought it actually cruel, as no reasons were ever given when a request for parole was turned down, often leaving a prisoner in a despairing limbo, at the mercy of a seemingly secretive bureaucracy.

The Parole Board had never been filmed and had refused all previous requests, but they finally agreed to a two-part study which was broadcast in 1979. We witness a part of a parole board panel’s discussion of a young sex offender who had committed a sexual assault on two young girls, followed by the then chairman of the Parole Board, Sir Louis Petch, whose comments illustrate only too well the assumptions and thinking at the time, and my critical conclusions on the parole system as practised then.

It is interesting to note, that all those critical concerns have since been met. Parole has become automatic for prisoners serving fixed term sentences over 12 months. Prisoners have the right to an oral hearing; the right to be represented; the right to know reasons for refusal; the right to appeal. The Parole Board is no longer an advisory body but a type of court in its own right, dealing with mainly indeterminate sentences and reviewing disputed decisions to recall prisoners back to prison. Whilst controversy remains over the Board’s ultimate independence, its transparency and role have profoundly evolved since our film in 1979.

In my experience of filming inside prison, I came to recognise how important Parole was to every prisoner. It took a long time, but I was finally able to persuade the Parole Board for England and Wales to allow me make a first time exploration of the parole system as it was practised in the 1970s. Filmed in several jails, the two parts reveal the cases of four men being assessed and evaluated for parole.I was not allowed to film a Parole Board Panel discussing their actual cases. The film also includes interviews with prisoners, prison officers, and scenes of a Local Review Committee panel discussing cases, as well as members of a Parole Board panel evaluating prisoners’ applications. I had a number of issues about the fairness, and even cruelty, of the procedures and expressed these concerns in my commentary for the programmes and in my questions during interviews.

Eileen, Lorraine and Kathy are the subjects of three films that focus on the pain and pressures on the wives and families of prisoners.

It became clear that families play an important role in the lives of career criminals, part-time criminals or even people convicted of one-off crimes. Many families genuinely suffer, caught up in a vortex from which they seem unable to escape. Some are enthusiastic players in a criminal sub-culture. However, as I recall, research suggested families being ostracised, enduring hardship and deprivation as well as having to be a support to their jailed man or woman.

In Part 1, Eileen awaits the verdict of the court as to whether her husband, John, will go ‘down’ again. John was on trial for various offences including possession of a firearm. The film details Eileen’s efforts to keep the family going, to keep herself going.

In Part 2, Lorraine gives birth to a son while her husband Steve serves a jail sentence for rape. Lorraine shares her pain and anxiety at what has happened - can she come to terms with it? How will her feelings for Steve develop?

In Part 3, Kathy and her four young boys await the release of her husband from a prison sentence. Can he adjust to their crowded council flat? Will he get a job? What will their future be?

Excerpt from an interview with Jamie Bennett, now Governor of HMP Grendon Underwood, for an article in Crime, Media, Culture

JB:

Your next film was Release… How did you come to chose to do that?

RB: I thought of the idea of Release - following someone literally as they were released from prison. I got in touch with the Prison Service and I remember going to Maidstone and, through the Governor, got in touch with one guy called Charlie Smith who agreed we could film him.

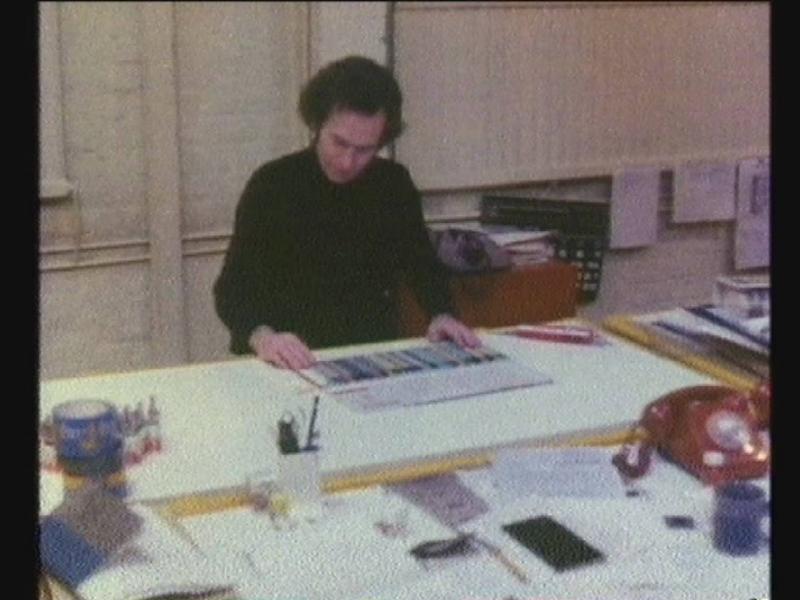

JB: Charlie Smith was very charismatic and a dominating character and was released… pursuing his ambition to become a commercial designer. Just that fact is in itself a very unusual story. Do you see his experiences as being generalisable or do you think it is something very specific to Charlie Smith. So is that particular film about release or is it about Charlie Smith?

RB: Both. An interesting point. Mind you, I am intrigued by the fact that you say it is unusual. In your experience of course of prisoners their aspirations, where they come from, what work they do, I suspect you know more than I do, but he was certainly unusual in any context. I think the film is about release, it is about paranoia, it is about how ill-equipped Charlie is and yet there is something very moving about his genuine aspiration to be an artist, and his desperate inability to take criticism, to do what most of us do, to roll with the punches. It throws up the hugely difficult task of preparing people for release, coming out, the trying again, adapting to society. I think it is always a big problem for the Prison Service and I know a lot of people are concerned about how do you prepare people for release, for the real world and all its pressures, problems and tensions. Charlie was articulate, and a very unusual character.

JB: Do you think having the crew with him filming actually had some benefit on his job opportunities? He did get a couple of opportunities, so do you think he was actually helped by this fact?

RB: I am sure you are right about that and indeed I tried to alert the audience [to that fact] in the film. I remember a commentary line saying we may have affected reality. He felt that Social Services would have treated him in a more unpleasant way. Undoubtedly the filming of him was unique, but contained within that unreality, I still think that Charlie’s mesmeric personality, the collision of his interest with the characters he met in the art world, certain sorts of truths emerged about him and his personality. I think it was intriguing that we were with him, and I think that people were amused and interested, and that may have helped him. That throws up the whole issue of capturing reality. To what extent were people behaving in a particular way because of the filming, even agreeing to see him because of the film and responding to him? Despite all that, I still think you get interesting realities emerging and interesting questions emerging about the challenge for an ex-prisoner trying to adapt to society, especially one so self aware and self conscious.

JB: How was he to work with?

RB: He was a very up and down character.

JB:Tell me what happened to him afterwards.

RB: We did the filming and at the end of it I did try to help. We got quite close as you can imagine. He got the job placement shown in the film but it proved short term and eventually he had to leave. I kept urging him to take a course. He tried and he got a place at the Chelsea College of Art, but unfortunately he couldn’t afford the grant, so he never went. And then literally six months after filming I got a call from him. He was at the Hayward gallery. I asked him how he was and he said he was ‘all right’, that he would ‘always try to ring and try to keep in contact if things went wrong.’ Anyway he said, ‘look after yourself,’ and I said, ‘look after yourself.’ I never heard from him ever again.

JB: The end is rather ambiguous, I feel. Charlie has secured a placement as a designer but also in the final interview he pessimistically predicts that he will be back in prison within 6 months. Does that reflect some of your ambiguity as well about the effectiveness of rehabilitative efforts?

RB: Yes, I think I felt very concerned for him that his over-sensitive response, his inability to take criticism, would tell against him. Charlie needed much more rehabilitative help to be able to use his talent, undoubted talent, for commercial ideas. He spurns the chance offered to him in the film. Also Charlie threatens to take revenge and go back to stealing if he is not allowed to become a designer. That is his bitterness and anger about society. So there was a tremendous mixture of things wasn’t there? I think because he was able, with my encouragement, to really let it all out, one got a rather extraordinary glimpse of a very interesting man, torn by various emotions, various needs; anger, self pity, desire, ambition, inability to take criticism. All of that may well be something a rehabilitative process couldn’t deal with. It may well be he was going all out to make sure it never happened, and that it all went wrong. I felt a self-destructive element within Charlie. But he was there on camera, expressing himself in a wonderfully interesting way.

JB: It raises for me some issues about rehabilitation. Whether rehabilitation is some kind of medical or scientific treatment or is it just a matter of personal choice and personal development? What would your observations be on that?

RB: I think it is a focus the Prison Service has got to put energy into. So many people go out, so many people come back, and reconviction rates are sad news for everybody really. It may well be that there is a limit to what anybody can do, if people are determined to carry on with a criminal career. It is what alternatives they get outside, what support they have outside the basics. Some people need clinical help for addictions, a huge problem, but also it is really about encouragement and whether there is a support system around people. The more isolated you are, I think the less chance you have. And again, perhaps at the heart of it all is whether a man or woman really wants to give life a go again and not take the criminal path. It is very complex and I think we should know much more about the factors that tip someone from one direction or another. In the end it has got to be a choice.

The idea for this film was to literally follow a man being released from prison and see what actually happened to him. We began filming Charlie Smith as he stepped out of the gates of Maidstone prison, setting out on a path to a new life and a new career as a commercial designer. Having, as he told us, cut all ties with his family, with no formal training, but with the help and encouragement of his probation officer, whom he loved. He was determined to do another ‘break-in’ - this time into the advertising industry.

The film documents Charlie’s struggle to find a job and get round the Ad agencies that he had contacted himself. Eventually Peter Mead, an advertising executive, gave him the chance to develop some ideas including ‘a lollipop with a personality’, offered him a £100 with an advance of £20 to get started. But Charlie misunderstands what he needs to do, is told this by Peter Mead, over-reacts, and walks out of a potential job. We see Charlie eventually given a chance with another design company working for the advertising industry. The film ends with Charlie threatening ‘society’: if after all this effort to go straight, he is not given a chance to design, he will go back to stealing.

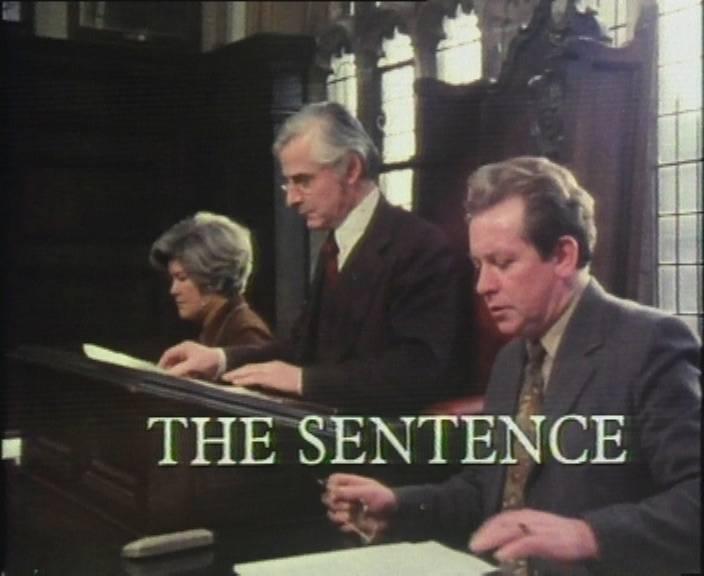

The Sentence was the first film I made on the criminal justice system in England and Wales. The experience led me to produce a body of work on the machinery of justice, and through that, notions of punishment. The films that I made in the seventies are now, in a sense, pieces of history – in some cases reflecting aspects of prison conditions and criminal justice that no longer exist.

The Sentence attempted to show the workings of a Magistrates’ Court and what sort of people became magistrates. I chose King’s Lynn in Norfolk and, to illustrate the judicial process, and concentrated on the actual case of a young married man called David with previous convictions for petty theft. David had been charged with similar offences, and this time, faced the prospect of a custodial sentence. We learnt from him about his alcoholic father, whom he said, ‘regularly and viciously beat his mother in front of him and his brothers and sisters’; of his need to drink; the failure of his business where he was happiest being his own boss; his wife and baby and, above all, his finding a job which David’s solicitor said was crucial to his chances of convincing the magistrates not to send him to prison. Sadly, David never got that job and went on to commit a further offence. The magistrates in the end gave him a six month custodial sentence.

I decided on a filmed reconstruction of David’s trial in the Tudor Magistrate’s Court in Kings Lynn, but instead of using actors - common enough today - I asked all the original participants in the case to repeat their roles during the actual trial, including the magistrates as well as the defence and prosecution solicitors.

Gaia Servadio had written a book called Mafioso, an intriguing account of the origins of the Mafia and its criminal impact on contemporary Western society. I approached Gaia and we decided to examine this reality on film by exploring the grip the Mafia had on one town in Sicily. We chose Alcamo, which was believed to be totally penetrated by Mafia and was famous in Mafia folklore, thereby enabling us to set the historical context for the origins of the Mafia and its parasitic emergence in Sicily.

For Gaia, the Mafia was not one secret criminal organisation but a mentality, a way of thinking, a way of life. We went on to detail the extent of Mafia control and influence in securing votes, construction, and domination of virtually every aspect of commercial activity in Alcamo.

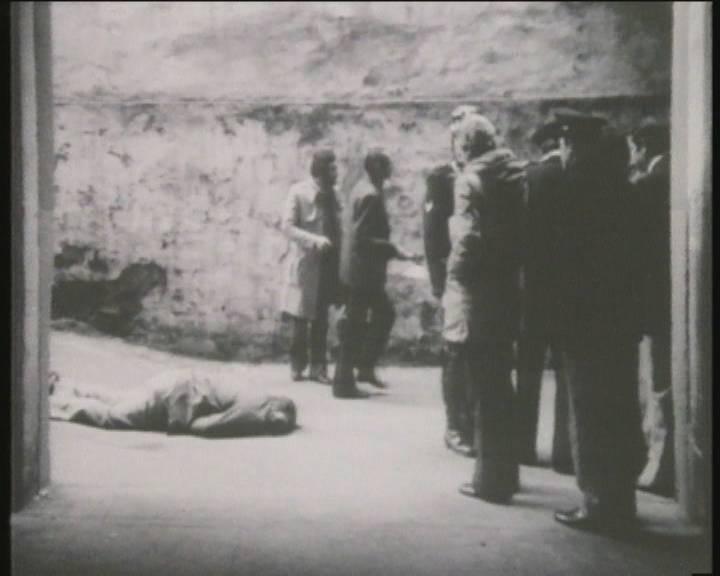

Gaia, the crew and I did not hide our presence - they were watching us and we went about our business of filming the town - interviewing the Mayor, a lawyer known to act for accused Mafiosi, the town priest and, through him, the passive role of the Church, local fishermen and the local trade unionist, who had bravely confronted them. We filmed the harbour, which had literally been bombed for fish, the motorways that were paid for but never completed, and estimated over 1,000 murders had taken place in Alcamo since the Second World War.

Castington YOI

Castington YOI

Mother visiting her son, an inmate at Castington YOI

Mother visiting her son, an inmate at Castington YOI

Darren leaving his cell in Castington YOI

Darren leaving his cell in Castington YOI

Darren leaving Castington YOI

Darren leaving Castington YOI

Darren boarding the bus outside Castington YOI

Darren boarding the bus outside Castington YOI

Aycliff YOI

Aycliff YOI

Programme 1: HMP Wakefield

Programme 1: HMP Wakefield

Programme 1: HMP Whitemoor

Programme 1: HMP Whitemoor

Programme 2: Leaving HMP Shepton Mallett

Programme 2: Leaving HMP Shepton Mallett

Programme 2: On licence - Trevor

Programme 2: On licence - Trevor

Programme 2: On licence - Gwylim

Programme 2: On licence - Gwylim

Programme 2: On licence - Joyce

Programme 2: On licence - Joyce

Strangeways 2001

Strangeways 2001

Strangeways 1957

Strangeways 1957

Aftermath of the Strangeways Riot 1990

Aftermath of the Strangeways Riot 1990

Strangeways 2001

Strangeways 2001

Title

Title

Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard

Reg Dudley and Bob Maynard

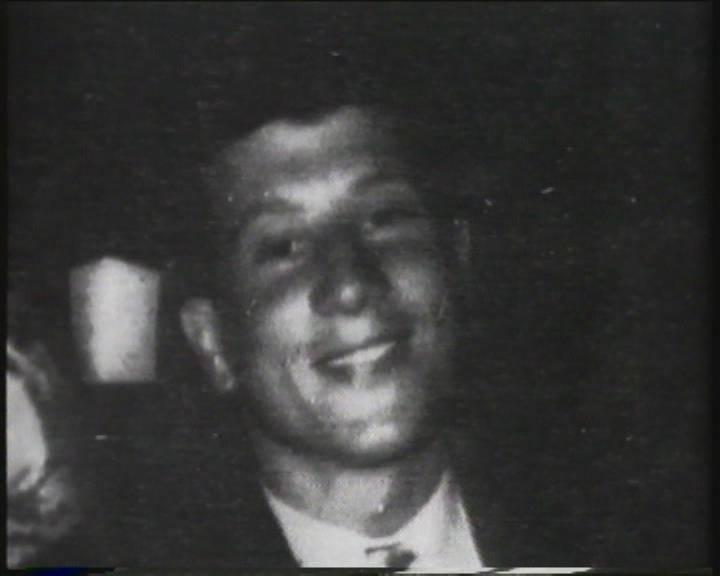

Billy Mosely - murder victim

Billy Mosely - murder victim

The Campaign

The Campaign

Reg Dudley filmed in prison

Reg Dudley filmed in prison

Bob Maynard filmed in prison

Bob Maynard filmed in prison

Title

Title

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

Life sentence prisoners under 21

Life sentence prisoners under 21

Young prisoner serving a life sentence

Young prisoner serving a life sentence

Women serving life sentences

Women serving life sentences

Lifer awaiting release on life sentence in HMP Wormwood Scrubs Hostel

Lifer awaiting release on life sentence in HMP Wormwood Scrubs Hostel

Lifer going out on day release from HMP Leyhill

Lifer going out on day release from HMP Leyhill

Title

Title

HMP Manchester - better known as Strangeways

HMP Manchester - better known as Strangeways

A Victorian jail

A Victorian jail

Inside Strangeways

Inside Strangeways

Entering Strangeways

Entering Strangeways

Prison Officers on landings in one of the wings

Prison Officers on landings in one of the wings

Xmas in Strangeways

Xmas in Strangeways

Dawn in the prison

Dawn in the prison

Count Claus Von Stauffenberg

Count Claus Von Stauffenberg

Count Claus Von Stauffenberg greets the Fuhrer at the Wolf's Lair a short time before detonating his bomb

Count Claus Von Stauffenberg greets the Fuhrer at the Wolf's Lair a short time before detonating his bomb

The judges enter the Berlin Supreme Court

The judges enter the Berlin Supreme Court

Roland Freisler, the President of the People's Court

Roland Freisler, the President of the People's Court

The court in session

The court in session

The cross examination of Count Schwerin

The cross examination of Count Schwerin

Ploetzensee prison where the conspirators were hanged

Ploetzensee prison where the conspirators were hanged

Title

Title

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

HMP Wormwood Scrubs

A prisoner awaiting parole

A prisoner awaiting parole

A view from a cell in the Scrubs

A view from a cell in the Scrubs

Parole Board Panel

Parole Board Panel

Charlie Smith leaves Maidstone prison

Charlie Smith leaves Maidstone prison

Charlie at work

Charlie at work

Charlie interviewed in his hostel

Charlie interviewed in his hostel

Title

Title

King's Lynn Magistrates Court

King's Lynn Magistrates Court

Reconstruction of David's trial

Reconstruction of David's trial

David

David

Title

Title

Alcamo

Alcamo

The harbour in Alcamo

The harbour in Alcamo

Vicitm

Vicitm

Gaia Sevardio

Gaia Sevardio

Gaia interviewing the Mayor of Alcamo

Gaia interviewing the Mayor of Alcamo

Murder

Murder